Each spring and fall, hundreds of millions of North American birds embark on one of nature’s most extraordinary events. Most travel at night, but if we were able to watch it happen, migration would appear to be – in the words of ornithologist Scott Weidensaul – “the largest, greatest natural spectacle on the planet.” Some migratory species travel shorter distances from wintering grounds in the southern US or Mexico while others spend weeks flying thousands of miles across hemispheres. The adaptations that enable dangerous long-distance travel are profound: some migrants have a protein in their eye that allows them to see the earth’s magnetic field; others can use half their brain at a time to sleep while flying. Birds that travel the farthest undergo extreme physiological changes including shrinking internal organs and doubling their body weight to prepare for their journey. The extra foraging time needed to pack on fat and muscle and the dangers posed by predators, severe weather, and human-made structures leave migrating birds highly vulnerable.

Despite the risk involved, migration has proven to be a hugely successful strategy. Two thirds of North American bird species migrate, primarily in response to food availability and nesting opportunity. The northern hemisphere experiences an explosion of protein-rich insects during the long days between May and August, which make ideal food for growing chicks. However, with warm weather arriving earlier each spring on average for the last several decades, the annual green-up of trees and shrubs and the seasonal boom of insects are arriving earlier as well. Climate change has also increased the frequency of severe weather events like “false springs,” which can spell disaster. How are birds adapting to these changing conditions?

New Spring Deadlines

Upon arrival at their spring nesting grounds, many birds depend heavily on the nutrition provided by insects. This calorie-dense food source provides vital energy for recovery, establishment of territory, and hungry developing chicks. As climate change pushes insect emergence earlier in the spring, birds face pressure to adjust their migration timeline or risk arriving exhausted from their journey after the peak hatching has already ended.

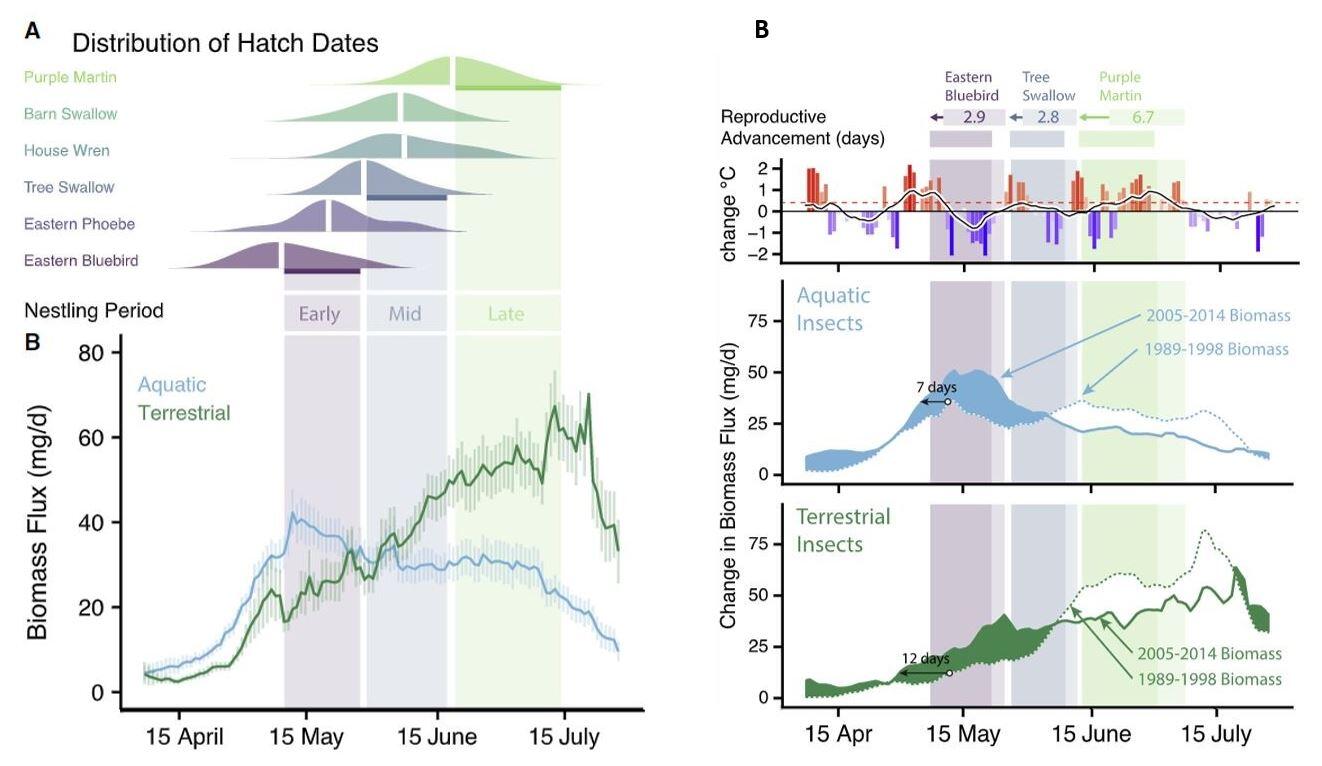

Differences between the timing of aquatic versus terrestrial insect hatch and their associated nutritional values can also have a grave impact on birds. Because aquatic insects (i.e., those whose larvae mature in the water) have 4 to 34 times more omega-3 fatty acids than terrestrial insects, aquatic insects are nutritionally superior. Many birds cannot simply replace them by eating terrestrial insects without sacrificing key nutrients that are critical to development and reproduction. A study of insects in Ithaca, New York found a change in both availability and species composition during a 25-year period from 1989 to 2014. Insects in general seem to be emerging 3-12 days earlier and booming over a shorter time period, creating a punctuated pulse of food available to birds. Aquatic insects seem to be peaking early and declining after May 15th. Insect hatches are advancing much more rapidly than bird migration and breeding, and bird species that breed later in the season like Purple Martins and Tree Swallows may miss critical foraging windows if they are unable to advance their egg-laying dates to keep pace.

As spring phenology (the timing of seasonal events) changes, many species of bird are indeed adjusting their migration habits. A 2020 study in the journal Nature Climate Change found that across several hundred North American bird species, most are arriving at their spring nesting grounds about one to two days earlier per decade. This difference equates to between five and ten days earlier than the birds would have been arriving in the early 1970s. Still, not all species are adapting equally.

Which species appear able to keep pace with an earlier spring depends largely on their preferred wintering destinations. Some, like American Robins and Eastern Phoebes, don’t travel very far. These species winter in Mexico and the southern US, regions that, although warm year-round, still experience seasonal temperature change. In the spring, these short-distance migrants interpret warm weather as a major signal to depart. Species in this category are proving more effective at adjusting to an earlier spring and timing their arrival north to match the rest of the ecosystem.

In contrast, long-distance migrants have shown less inclination to adjust their migration timeline. These birds, including tanagers and many warblers, overwinter farther south in neo-tropical countries like Cuba, Colombia and Venezuela. Closer to the equator, this part of the world sees minimal seasonal temperature fluctuation, and migratory birds instead rely on permanently fixed signals like their internal clock for their cue to migrate.

Even for species that have been successfully keeping pace with spring, their efforts may come at a cost. Rather than leaving their wintering locations earlier, some birds have been adapting to early warming by attempting to make up time during other phases of migration and breeding. Wood Thrushes are arriving north only a few days earlier but hatching their chicks about 22 days before they would have in 1960. Other species seem to be starting their journey at the same time as historically observed, but are accelerating the pace to catch up. Both of these rushed strategies can place exhausting stressors on birds already burdened with a difficult task.

False Springs

Sometimes, arriving earlier in the spring may cause birds more harm than good. Unpredictably extreme weather has become a hallmark of climate change. When a prolonged period of late winter warmth plunges back into freezing temperatures, the ecosystem goes into shock. Plants suffer frost damage to delicate buds and migrating birds that have raced north may face snow and freezing rain at the end of an exhausting journey. Insects go dormant or die, leaving the birds that depend on them with no food to replenish their strength. False springs can also stunt native plants, resulting in reduced quantity and quality of fruit and seed crops later in the season. In this way, damage from spring cold snaps ripples into the fall when the fuel birds need for that migration south is reduced.

Surprising Findings

Although the results are less straightforward than spring, climate change is still affecting the timing of fall migration. A warmer climate is bringing longer summer weather, and as we might expect, birds that typically leave late to fly south are migrating even later. Surprisingly, the opposite is true for species that leave earlier. The earliest-departing fall migrants are shifting their travel schedule sooner, resulting in a lengthening of the overall migratory period. According to one study, the fall migration season now stretches out about 17 days longer than it did 40 years ago.

While timing of migration is shifting in general, discrepancies in the behavioral responses between males and females have also begun to emerge. A study published last year examined 36 migratory bird species over the last 60 years. The authors found that adult males have shifted their average arrival times by over five days, while adult females are lagging behind with just under a four-day shift. Historically, males arrived a bit earlier in spring, and now this gap appears to be widening. Males of many species winter a bit farther north than their female counterparts, so one explanation is that higher latitudes allow them to stay more attuned to the changing timing of spring weather.

Perhaps most interestingly, climate change seems to be prompting adjustments to birds’ physical proportions. A 2021 study that reviewed 70,000 museum specimens across 52 North American migratory species revealed that over the last 40 years, birds’ body mass generally got smaller while their wingspans got longer. This change may allow birds to shed body heat faster as the climate warms, or there may be other benefits we have yet to understand. Regardless, when overlaid with multi-decade weather radar data tracking climate change, there was a strong correlation between these physical changes and the timing of rapid warming events. Since wing length is associated with more efficient flight, researchers expected species with the greatest increases in wing length to be those that advanced their spring migration the most, but found no such trend.

All of these expected and unexpected trends – insects hatching earlier, male birds shifting migration faster than females, certain migrants leaving earlier in the fall, and physical changes to birds’ bodies– illustrate the complexity of the systems being affected by a warming world. Many factors are likely co-interacting, and we are just beginning to understand them. While the shifts we are observing highlight the added stressors birds must face, their ability to rapidly adjust behavior in response demonstrates an impressive resilience. Being witness to nature actively trying to prevail certainly brings hope for the ability of the creatures we love to withstand the changes ahead.

There are many ways to get involved with nature’s most amazing feat. Check out Audubon’s Bird Migration Explorer, an interactive digital tool that follows hundreds of species on their epic journeys and helps users learn about the challenges they face along the way. You can also explore a forecast for the intensity level of night-time migration at birdcast.info. If you are interested in contributing to the body of knowledge around bird migration, population sizes, and locations, submit species observations to the community science platform eBird.org. Next month you can also participate in a Birdathon, where local teams count as many bird species as possible in a 24-hour period to raise money for conservation (and for fun)! Happy migration season.

This article was written collaboratively by Audubon Vermont staff: Matt Hallahan, Cassie Wolfanger, and Margaret Fowle.