President John F. Kennedy, at whose inauguration Robert Frost delivered a poem, said of the four-time Pulitzer Prize - winning poet, "He has bequeathed his nation a body of imperishable verse from which Americans will forever gain joy and understanding." Although Frost is perhaps better known for his 1916 poem, "The Road Not Taken” - I like to think he was referencing a lesser known poem that Frost penned in the summer of 1929 titled “The Oven Bird.” The first three lines of this sonnet go as follows:

There is a singer everyone has heard,

Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again…

I’m particularly fond of this piece, not because I have an especially fine taste in writing nor a natural affinity for poetry, but rather because Frost celebrates one of the most common - yet too-often overlooked - songbirds that inhabits Vermont’s sugarbushes during the summer. Frost’s poem is an ode to the Ovenbird ( Seiurus aurocapilla) - a migratory songbird and member of the family Parulidae (New World warblers, or “wood-warblers”). In the first line - “A singer everyone has heard” - Frost makes reference to the fact that nearly everyone who has walked through deep woods in the Northeast is perhaps familiar with the Ovenbirds’ song, even if they can’t identify the species by appearance. Vermonters are likely familiar with the Ovenbird’s emphatic tea-cher tea-cher tea-cher song emanating from some hidden perch in the mid canopy. I like to think Frost was very intentional in his wordage, given that he didn’t describe the Ovenbird as a creature “everyone has seen” or that “everyone has known.” Although Ovenbirds are relatively common in areas with mature, intact forests (Partners in Flight estimates their global breeding population to be 22 million), their olive- brown coloring, small size (they measure 6” from head to tail) and tendency to forage quietly in the leaf litter mean they are more-often heard than observed. Additionally, although observant outdoor enthusiasts may be familiar with ovenbirds perching and singing, we still don’t understand a whole lot about their vocalizations. For instance, Ovenbirds have been found erupting into song at dizzying heights above the ground. This usually happens in the dead of night when males launch above the canopies of their forested territories, singing an ecstatic jumble of notes - with only the final few notes resembling the usual tea-cher tea-cher song. There is also evidence that Ovenbirds use variations in the structure of their signature “teach-er” phrase to identify offspring, parents, mates, and neighbors. To us mere humans, their tea-cher chant sounds like two flat notes, but it is in fact composed of up to 5 separate ones! The number of notes in each part of the phrase and their pitch helps identify individuals. As their vocal repertoire highlights, there truly is more to Ovenbirds than meets the eye (or ear)!

In the lines that follow, Frost’s sonnet describes (and quite accurately I might add!) the situation in which an Ovenbird is often encountered: in the middle of the woods, in the middle of summer. The second line in particular - “a mid-wood bird” - likely references the fact that Ovenbirds are particularly sensitive to forest fragmentation and to disruptions caused by road-building, industrial noise, and logging. Their ability to establish territories and breed successfully depends on the continued existence of large, undisturbed mature forests. Numerous studies have found that Ovenbird nesting success drops precipitously as forest cover diminishes in fragmented landscapes. This relationship is due to the fact that nest predation and parasitism (primarily by Brown-headed Cowbirds) is greatest in areas closer to the forest edge - a so-called “edge effect.” As forests become fragmented - whether it be through logging, the expansion of suburban development projects, or field-based agriculture - the proportion of area conducive for species that can thrive in edge-type habitats increases at the expense of prime real estate for deep-woodland birds (including Ovenbirds, Pileated Woodpeckers, and Yellow-throated Warblers, just to name a few). Like islands in the ocean, islandlike fragments of forest are known to lose species - including Ovenbirds - at predictable rates owing to fluctuations in population size and the costs of such edge effects. Ground-feeding, insectivorous birds like the Ovenbird are also among the species most-likely to disappear as the size of a forest patch decreases, likely because these birds thrive in areas with a deep leaf layer to forage (and nest!) within - a direct result of having a dense forest canopy coupled with a good dose of shade.

In the third line, Frost’s poem alludes to the fact that male Ovenbirds sing rather late into the breeding season compared to other songbirds, which is why the “solid tree trunks sound again.” Male ovenbirds arrive from their wintering grounds in Mexico, Central America and the Carribean in early May, approximately two weeks before the arrival of females in order to set up and defend territories from rival males. To defend their abodes, males often counter-sing, in which one male’s song is immediately followed by his neighbor’s, giving the appearance of a continual song sung by two birds. In addition to warning intruders, the male’s song is an important piece of criteria used by females during mate-selection. Research has shown that females preferentially select males with longer and louder songs because these males usually inhabit superior territories and are in better physical health than males singing shorter, disjointed songs. Although ovenbirds breed from late May to July, males continue to sing through August, long after other warbler species have since stopped broadcasting territorial melodies. As Frost indicates, although the springtime dawn chorus of birdsong may have faded into memory, the ovenbird continues to offer his daily chants well into the heat of summer.

Now, I would be amiss if I didn’t mention how the Ovenbird received its unique name, which Frost (sadly) neglects to mention in his poem. Etymologically speaking, the genus name - Seiurus - is from Ancient Greek seiō, which means "to shake", and oura, which means "tail.” This references the fact that alarmed ovenbirds often lick their tails from a half-raised position. The latter half of the Ovenbird’s scientific name - aurocapilla - comes from Latin and means "golden haired" - a reference to the bird’s orange streaks which run across the top of its head. The origins of the Ovenbird’s common name is particularly interesting in my opinion, because it refers to the manner in which females of the species construct their nests, unlike many other warbler species which tend to be named according to their coloration (e.g. Black-throated Green Warbler, Black-throated Blue Warbler, etc.), feeding preferences (e.g. Worm-eating Warbler), geographic distribution (e.g. Canada Warbler, Tennessee Warbler, Kentucky Warbler, Cape May Warbler, etc.) or perhaps most-boringly dead white men (e.g. Townsend’s Warbler, Swainson’s Warbler, Kirtland’s Warbler, etc.). Instead, the Ovenbird is named for its dome-shaped nest, which closely resembles a Dutch oven.

Female ovenbirds construct this oven-like nest in thick leaf litter on the open forest floor, typically in a spot near a small break in the canopy, such as where a large tree has fallen. The Ovenbird’s nest is the epitome of functionality - complete with an overhead “roof” of leaves to aid in concealment and protection against the elements, as well as a large oval side entrance generally facing downhill, which facilitates the rapid escape of the mother bird should a predator (or ambling hiker) walk close by. What I find particularly enthralling about nests is that these physical constructions reflect the inner workings of a bird’s mind - shaped by thousands of years of coevolution in the habitat each species calls home. In the case of the Ovenbird, the choice of nesting material reflects many of the plant and animal species that co-inhabit Vermont’s forests - from deer to certain tree species comprising the overhead canopy. To begin, the female clears a circular spot on the forest floor litter (no small feat for a 6” long bird!) and over the course of five days weaves a domed nest composed of dead American Beech, Sugar Maple, and Ash leaves, grasses, stems, bark, and hair. To begin, she creates a warm inner cup - just 3 inches across and 2 inches deep - lined with the finest of tree roots and deer or horse hair, oftentimes plucked from the live animal itself! Next she constructs the outer dome - measuring approximately 9 inches across and 5 inches high - which is camouflaged with leaves and small sticks. Although the nest has a humble appearance, it’s incredible to think that the inner and outer layers are constructed of different materials and that each has a different purpose - for warmth/cushioning, and camouflage/protection from the elements, respectively. And to think - all of this work is completed by a bird without the use of hands, fingers, or opposable thumbs! Having marvelled at Ovenbird nests in person, I can only imagine how different Robert Frost’s poem would have been had Ovenbirds learned to use excavators and all the bells and whistles human engineers have at their disposal! Now somebody should give these humble warblers an engineering degree already...

Identification Info

ID: Compared to other warblers, Ovenbirds are rather rotund and appear “wide-eyed” with their round, black pupils and white eye-rings (this eye-ring can be used to distinguish the species from similar-looking Louisiana and Northern Waterthrushes, which both have light eye stripes below their pupils as opposed to a complete white eyering). Males and females look nearly identical (females are said to be slightly duller in color); both have white chests lined with bold black spots, as well as two black stripes running over the top of the head (the crown) interspersed with orange streaks (although the crown color may be challenging to see) and pinkish legs. Ovenbirds are olive-brown on their upperparts, including their tail feathers, backs, wings, as well as both sides of their head. Aside from their appearance, Ovenbirds can easily be identified by their signature “tea-cher tea-cher tea-cher!” song that increases in intensity and volume with each note. Typically males of the species sing this tune loudly from an exposed perch positioned high in the understory. Their eggs are white with reddish- brown speckles and measure 0.8-0.9 inches long by 0.6 inches wide.

Habitat: Ovenbirds nest and forage in expansive tracts of mature deciduous or mixed coniferous-deciduous forest from the Mid-Atlantic to northeastern British Columbia. They prefer to establish territories in areas where the understory is well-shaded, thus facilitating the development of a thick decaying leaf layer , which provides better habitat for their preferred invertebrate prey. Although they most commonly forage on the ground, Ovenbirds prefer summer breeding grounds with a tall tree canopy (between 50-70 feet above the ground), from which they sing and survey their territories. During the winter months, Ovenbirds inhabit a greater diversity of habitats, ranging from mangrove forests to abandoned agricultural lands and even coffee plantations.

Diet: Ovenbirds feed mainly on insects, including caterpillars, flies, ants, and many different types of adult beetles and their larvae. Ovenbird nestlings have a particular sweet (egg)tooth for ground beetles. During the winter months when they migrate south to Florida, the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America, Ovenbirds consume grubs and insects near water sources in addition to seeds. As opportunistic foragers, Ovenbirds can shift their foraging tactics to utilize seasonal and pulsed food sources including outbreaks of forest tent caterpillars (this species is of particular concern to sugarmakers, as these native caterpillars can defoliate and damage large swaths of a sugarbush forest).

Feeding behavior: Ovenbirds often forage by walking through leaf litter or along logs as they search for invertebrates within low-lying vegetation. They walk with a hesitant gait, bobbing their heads ever so slightly as they glean and probe insects from leaves, twigs, and the forest floor.

Fun Facts:

1) A group of ovenbirds is collectively known as a "stew" of ovenbirds.

2) As if they can’t contain their excitement, young Ovenbirds often hop as they forage.

3) The oldest confirmed Ovenbird was at least 11 years old when it was recaught and re-released in Connecticut.

You can be a friend to the birds of the sugar bush by supporting maple producers who are certified through the Bird-Friendly Maple Project, or by following the Project’s sustainable forest guidelines and earning the stamp of approval for your products.

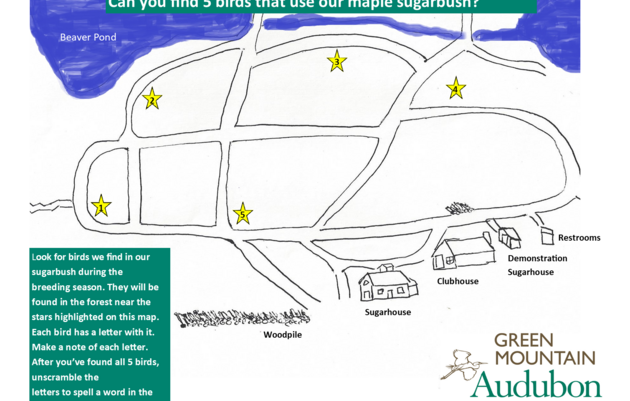

#AudubonMapleMagic scavenger hunt!

You found the letter "M" !