And I mean it. The Dark-eyed Juncos, American Robins, and Northern Parulas that greet me each morning as I wake up are incredibly awe-full. Ovenbirds, Red-eyed Vireos and Black-throated Green Warblers’ awe-full songs fill the air covering the dew dropped grass during the morning promenade. And soon enough the prehistoric Great Blue Herons silently glide overhead while the mystical echoes of the Hermit Thrush fill the dawn atmosphere - just as awe-full as all the others.

I was introduced to the concept of awe this past year through an assignment for a class I was part of at the University of Vermont: The Fellowship for Restoration Ecologies and Cultures (FREC). The year-long course covered a host of topics such as ecological restoration techniques and working landscapes. Though one everlasting concept has been that of awe. The feeling of awe, as described in the NPR podcast On Point is, “that feeling beyond happiness. Past wonder, to the sublime." The podcast further explains the sensations of awe and how, in many ways, it can improve your mental and physical wellbeing. What resonated with me was that awe is experienced in varying magnitudes from the breathtaking views of the Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone and El Capitan in Yosemite to the feeling of waking up with the sun on your face to the first bite of your favorite food.

My first year of college I struggled to find my place. I turned to daily walks around town as a quest to find places that brought me joy. I quickly found it in the nearby natural area when I walked in and was instantly greeted by the Black-capped Chickadees, White-breasted Nuthatches, and Pileated Woodpeckers. Just as the leaves drifted from the trees and winter descended upon us, the birds moved away. After the grueling winter, the first patches of green arrived outside my dorm and the American Robins returned. This felt like an old friend reaching out to catch up - familiar, yet new and exciting. This, I realized, is what awe feels like. Now each year I await the first signs of American Robins hopping around, feeling relieved that spring and sun are finally on their way. They remind me that I am part of a larger system, that no matter what I am whole with the birds and the breezes rustling the branches and the water rushing over smooth river stones.

Now, three years later, comes my internship with Audubon Vermont and Mark LaBarr, Conservation Program Manager, as a Priority Species Conservation intern. I got this opportunity through my course, FREC. Oddly enough, I never considered myself a “bird nerd,” but the thought of getting to work directly with birds sounded incredible. I knew I had an appreciation for our avian kin and held deep gratitude for the awe they brought me in the spring that pulled me out of the dreaded winter slump. However, I never could have anticipated the awe that this experience has brought me this summer. Slowly motoring up to Popasquash Island and watching the masses of Common Terns, Ring-billed Gulls, and Caspian Terns soar above and hear the uproar of their squeaky calls is something like no other. Each time we visited there would be something new to see, including the tern chicks that had hatched a mere hour before we arrived. The small but mighty colony of Common Terns defending their perfectly camouflaged trio of eggs from the intruding pack of gulls is a sight of such awe, representing all the nuances of conservation.

The first time I heard the bizzz-buzzz of the Golden-Winged Warbler was a day that will stick with me forever. It was my first day on the job and Mark and I were driving to Southern Vermont to work with the Nature Conservancy of Vermont to repair a Motus tower. Suddenly, Mark hears the signature bizzz-buzzz of the elusive Golden-winged Warbler through the car window and without skipping a beat pulls over and jumps out to search for the bird. “This habitat,” he says pointing, “is perfect for these warblers because of the shrubby area up front and the forest in the back.” - a line I would hear many times again. That day I was filled with awe. Awe at the scenery I had never seen before, even after living in Vermont my whole life, and at the excitement someone could have over a bird call that I could have sworn was just a beetle.

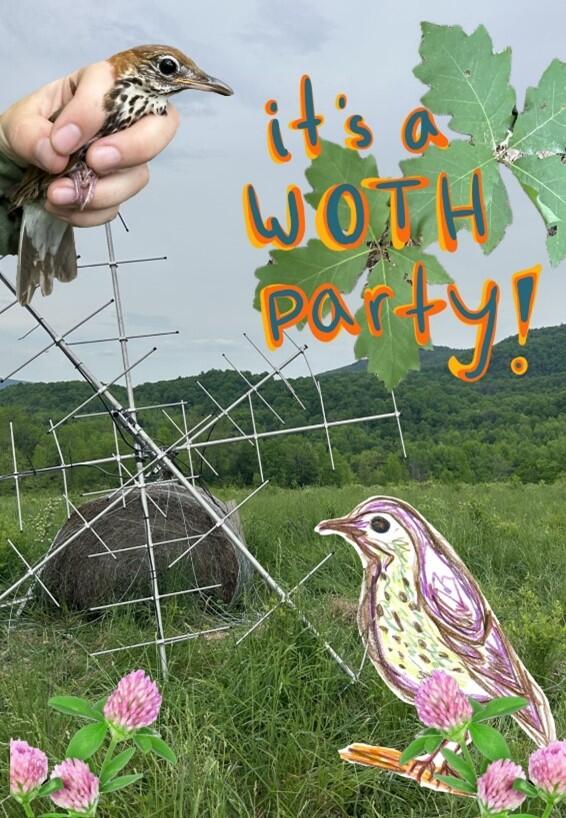

The most awe-full of all was the Wood Thrush project we worked on. “WOTH Party,” lovingly titled by Mass Audubon who initiated the project, deploys nanotags on Wood Thrush to better understand their movements and ecology. The first WOTH (code for Wood Thrush) we tagged was at Wake Robin in Shelburne not even fifteen minutes after we set up the mist nets. As I recorded the age, sex, and weight of the bird and used a super high-tech device (crochet hook) to weave the looped harness onto the legs, I felt so professional. Catching the next five WOTH was not as simple. We arrived at each site at 7 a.m., hoping they would fly right to us as soon as we got there. Unfortunately, this is far from what happened. Each bird took their sweet time and started singing and flying around at 10 a.m., a quite relieving song to hear after several hours of sitting in a cloud of mosquitoes. Through tagging all the WOTH Mark and I became experts at donning the birds with their new, red carpet-worthy nanotags.

These three awe-full escapades quickly became the highlights of my summer. Though this was not all. There was also the time on the lake where the boat motor almost died when we were miles from the shore (we were about ten-minutes to the boat launch and the motor actually broke down as soon as we got back). I learned how to band birds which includes gathering the age, weight, sex, and molt of the bird and even got a WOTH named after me! Along the way I met many incredible people across the state, lugged mist net poles through thick jungles (Vermont deciduous forests) and got attacked ruthlessly by swift jaguars (mosquitos and deer flies). I learned how to find awe in everything - I found it in the perseverance of the Common Terns, the way the smell of the forests changed over the summer, and even sometimes in the persistence of the mosquitos trying to bite through my thick work pants (good on them for trying). As described in the podcast, feelings of awe can change how you perceive the world and your place in it. Through this internship, my perceptions of bird conservation grew and morphed into something I could never have imagined for myself. I found my place as a newfound “bird nerd” and grew my confidence in the world of ecology and conservation - all through moments of awe.