What makes a forest most productive for a syrup producer? What makes a forest good habitat for animals? Why is tree diversity important to a forest? How do decomposing logs help an ecosystem? This month in UnSchool we answered these questions and more while exploring the trees in the Audubon Sugarbush.

Of course, for a maple syrup producer, you will get the most syrup if you have a forest with only maple trees, but what about the animals that live in that ecosystem? The students said that animals need trees for shelter, dead trees to nest in, and places to find insects to eat. Ecosystems need diversity.

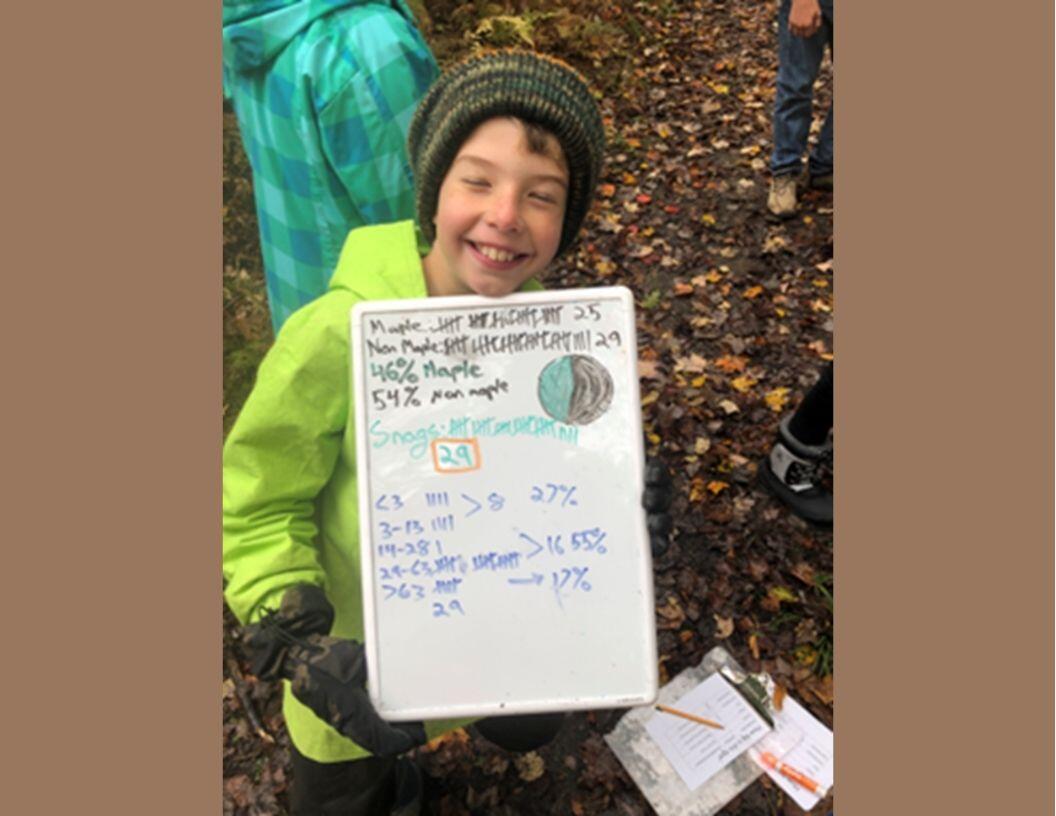

With the older half of the class, we collected data in transects, walking out into the woods in all directions like the spokes of a wheel. First, everyone learned how to identify a maple tree and counted how many trees on their transect were maples and how many were not maples. For a bird-friendly sugarbush we want at least 25% of the trees to be non-maple. Next, they counted the number of standing dead trees, or snags, along their transect. The kids said that these are important because fungi grow on them, woodpeckers drill into them, squirrels hide nuts in them, and insects live in them. Ideally, there are at least two snags per acre of forest. Lastly, we talked about the importance of tree size diversity. If all the trees in a forest are really big and old, there may not be enough light on the forest floor for the small vegetation that animals eat. Small trees and shrubs also provide shelter for animals. Having a diversity of tree ages and sizes in a forest allows for the ecosystem to continue to thrive as old trees fall and young ones take their place. All the students went back out along their transects to measure all of the living trees from the little saplings to the tall giants. Ideally, 25% of the trees in a sugarbush are smaller than 13 inches in circumference.

This project required students to work together, take turns, solve problems, make inferences, and do math. When we came back together, we looked at our data. In total we found that 54% of the forest was not maple, we found 29 snags, and we found that 27% of the trees were less than 13 inches in circumference. Our sugarbush is bird friendly!

While the older half of the class studied one section of the forest, the younger half studied another. They learned about the stages of the life of a tree, all the way from a seed falling to the ground, to a decomposing log. Once they figured out the order that the stages go in, they did a scavenger hunt to find as many of the stages as they could in the forest. A healthy forest ecosystem will have all the stages of a tree’s life represented in it. Once they’d done that, they explored the forest floor to find which animals use rotting logs and broken branches as homes. Trees are beneficial to an ecosystem even when they are no longer alive. The group found plenty of worms, salamanders, insects, and fungi. Based on all the animals they found and the variety of tree ages, they said that this was a good forest ecosystem!

After lunch the group took a break from trees to explore Beaver Pond for some free play time. We brought nets to scoop and found several Eastern Newts, but the most exciting find at the pond was a muskrat that had recently become dinner for a predator, likely a coyote or fox. It was in the grass next to the pond. The kids were fascinated by it, coming over to look and learn about it.

When we got back from the pond, we split into three groups and gave everyone one last challenge: finding the biggest tree in the sugarbush. We all dashed out into the forest with our tape measures. During our closing circle, we shared the sizes of our biggest trees. The winner was 115 inches in circumference!

If you have a tape measure at home, go out in your yard or local park and let us know the biggest tree that you have. While you are at it, you can assess the quality of your forest by looking for tree species diversity, tree size diversity, snags, and logs. Look under the logs to see who may live there. Below is a guide to trees commonly found in Vermont. How many can you find near your home?