Each morning as I put my field clothes on (water-resistant, breathable pants, long, breathable sleeves, a ballcap for sun protection) I can already feel the damp, chest-level field grass coating my outfit with fresh morning dew. Today is no different - it’s the middle of June and Bobolinks are busy raising their young in fields that ten years ago likely would have been cut by now. This day in particular we are heading out with Dr. Allan Strong, the UVM professor/ornithologist behind the Bobolink conservation movement in Vermont and an original founder along with Dr. Stephen Swallow. Allan, in 2013, also helped partner UVM with The Bobolink Project. Altogether, our crew for today is another intern, Simran, Dr. Strong, and Audubon Vermont’s Conservation Fellow, Cassandra, and myself. Allan is here for this particular day in the field but I intern under a Conservation Biologist for Audubon Vermont, Margaret Fowle, who surveyed a significant portion of the Bobolink fields this year and with whom I spend most of my time surveying.

We often rendezvous at the Ferrisburgh Park and Ride around 4:30 am, but today is an early trip so we’re meeting at 3:30 am. I make it to the park and ride where we carpool the rest of the way to the first farm we’re visiting. The sun peeks out over the horizon as we first arrive. Service is spotty so we’re relying on poorly rendered maps, spotty service and spottier memory. We manage to find a piece of the property that might have some Bobolinks but as Allan notes, “Too small and narrow.” Bobolinks prefer to breed in circular/ovular fields over narrow, rectangular fields or fields or complex fields with lots of edges. As I stare at the small, narrow field, I ponder all of the other fields we’ve walked and the hundreds of acres enrolled in the program. As of 2020, there were 755 acres enrolled in Vermont.

We’re here today because of The Bobolink Project. The Bobolink Project began in 2007 in Rhode Island. By 2011, the project had branched into Vermont under the watch of Allan Strong and Stephen Swallow. Essentially, the simplest goal of the project is to pay farmers for delaying their mowing schedules until grassland birds have finished breeding and their young have fully fledged (early August). The project funds are solely provided by donors - which has been one of the most amazing aspects of the project. It reveals that that Bobolinks are a flagship species (a charismatic, conservation mascot that is a significant source of conservation funding and, therefore, a powerful aid to other species with which it shares habitats - like pandas, or tigers). Other ground-nesting obligate species like Eastern Meadowlarks, Northern Harriers, Savannah Sparrows, etc. are aided by The Bobolink Project and the Bobolink’s role as a flagship species.

The next step is where we, Audubon Vermont, come in and where we get soaked and starry-eyed: the field surveys. At our first field, which we go to because a landowner enrolled their land in the program, Cassandra quickly points out a centuries-old graveyard. We dance between some trees and creep into the graveyard. We spend a few extraordinary minutes resurrecting buried names and feeling small, but alive. The graveyard experience felt unexpectedly similar to our Bobolink work. Seeing the gravestones was a reminder of how short life was, “1867-1895”, and how valuable every hyphenated time period really is. We all chose to spend a portion of our hyphen soaking wet and sleepwalking because we’re passionate about the Earth.

We leave the graveyard and walk back up to our cars. Upon returning to our vehicles, we see the landowner waiting for us. He’s sporting a friendly smile and a thick Vermont accent. Allan and he talk for a bit about the project and the farmer asks, “What kinda birds did you see?” and then proceeds to mention how many whip-poor-wills he sees while out hunting or in the early morning. The question was genuine and it was very cool to hear. The Bobolink Project subsidizes farmers for setting aside their grass-cutting during the crucial 9 to 11-week period when Bobolinks will be breeding. This aspect of the project casts the landowners/farmers’ intentions as monetary intentions (which, in part, they are) but it’s impossible to know the genuine curiosity and interest most of them possess until you talk to them. Every farmer we talked to throughout the process asked for a list of birds we heard, simply because they were curious. As Jon Atwood, director of Mass Audubon (the homebase for The Bobolink Project) said, “some participants are interested in birds and might delay mowing their fields even if they didn’t get paid for it.”.

We drove to a field soon after and, sure enough, we heard the “R2-D2”, mechanical bird song that Bobolinks make. The sound carries through the air smoothly and sends a soft buzz into the air above us. The closer we get, the more Bobolinks we hear, and the less we hear anything else. The field is just through some trees as we see the glowing cream-color of the male Bobolinks’ napes and the popping white on their backs as they burst through the sky. We see three chasing one female which is a yellow-brown color (drab for disguising the nest), and she gives attention to none of them, instead slipping into the tall grass - likely back to her young.

Allan points us toward the far edge of the field, just in front of some conifers. We line up across the field to perform our transects and Allan holds up his hand like a drill sergeant. He looks left, then right and then lowers his hand forward as a sign to start moving. We move forward; we’re on the frontlines of war. Within moments, the field turns into pure Bobo-madness. They’re flying overhead, beeping and bopping, chasing each other in frantic circles, flying rapidly in and out of each of our zones, popping out from the grass to our left and landing to our right; we’re surrounded now and we know it. It’s amazing to be in the heart of a Bobolink colony like this. All we can do is smile and look at each other.

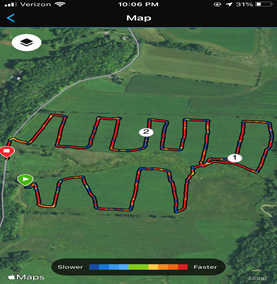

We swim through the chest-high grass, counting Bobolinks as they cruise by. Communication is key, so we look at each other to see who counted which bird: speaking with our fingers and facial expressions. As we patrol the field, we hear a Red-tailed Hawk screeching at us from the trees to our left. My particular route takes me into a ditch so I lose sight of the group for a bit but as I emerge from the reeds I see them still traveling along the same line as before. We eventually reach the far side of the field and compare notes, calculating our final count based on how many Bobolinks we thought had overlapped into another’s zone. As we finish, we hear two Savannah Sparrows in the adjacent field; Savannah Sparrows are another grassland bird that needs protected grasslands like the one we’re on today. Once we finish our final count, we head back to our cars.

As we drive to the next field, Allan and I discuss the project and he points out the decline of agriculture in Vermont and how practices are changing; this agricultural decline has effects on the Bobolink Project too. In the beginning of The Bobolink Project, most of the land enrolled was agricultural land but now that’s not necessarily the case. This change in enrollment has thrown the economics of the project into a bit of disarray - landowner compensation has gone down because non-agricultural landowners don’t necessarily need as much compensation since their economic sacrifice is not so significant. The economic model itself is a reverse-auction style. As the name implies, this means that the seller and the buyer have reversed roles where there is only one buyer and many sellers. The landowners bid on the lowest per acre payment they’re willing to accept. Once land is enrolled, the fields are ranked by value/potential for Bobolinks. The fields are evaluated by three categories: size, surroundings and shape. The lowest bid is guaranteed to be entered into the program and, since this is a fixed-price reverse auction, the lowest bid will be equal to the highest chosen bid once the bidding has ended.

The economic numbers bouncing around in my head slowly disappear and our conversation quiets as a sprawling field comes into view; it’s the largest one yet. We leave the vehicle and immediately hear the rustic calls of the Bobolinks, mixed with a distant Eastern Meadowlark and a few Savannah Sparrows. For a moment, I feel connected to the land in a new way and my feet feel heavy as they crush the auctioned grass. As the Bobolinks surface from the field, we take our positions at the field’s edge and I watch the flying droids from below. I feel both large and small at the same time; I feel consequential and inconsequential at the same time as we march forward in the name of conservation.

For more information on grassland bird conservation in New England, see: https://www.audubon.org/magazine/summer-2021/how-farmers-new-england-make-hay-bobolinks