When incorporating wildlife habitat considerations into existing farm practices, it is possible to identify mowing timeframes or grazing timing and intensity in which bird conservation and producer objectives can align. Audubon Vermont’s Bird and Bee Friendly Farming Program is learning from and testing strategies to promote the creation and improvement of on-farm habitat for birds and pollinators, including grazed pastures.

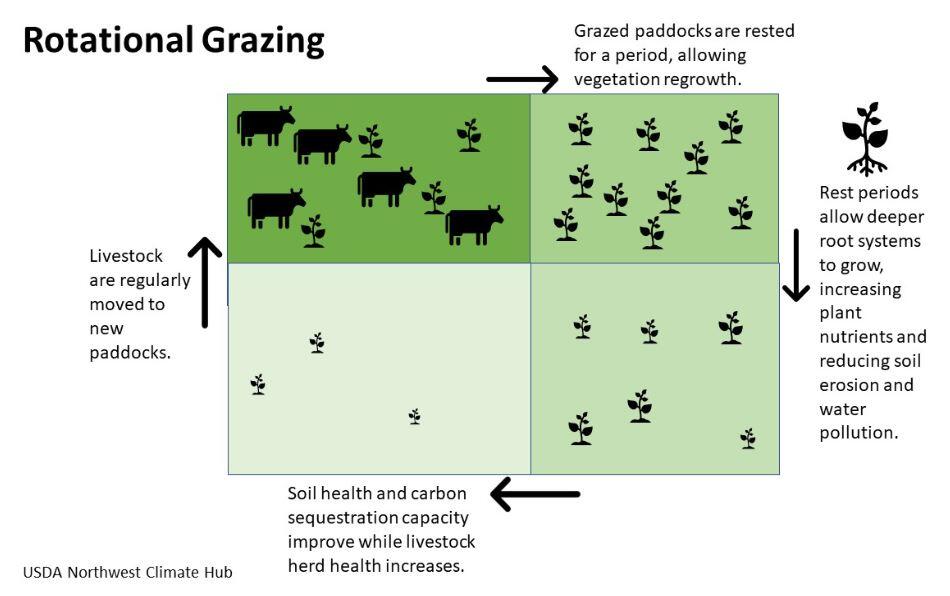

Intensive Rotational Grazing Systems

In part one of this article series, we discussed how intensive rotational grazing divides pastures into small sections that are grazed for short periods with high density herds before being moved frequently and how this may improve vegetation structure and reduce nest trampling risk for birds. These grazing systems are typically located on productive sites, such as the lush pasture land in the Champlain Valley of Vermont. Cows are often milked twice a day and moved to a fresh grazing strip as often as every 12 hours after each milking, but no more than every couple of days. Imagine it is like reading the words on a page from left to right all the way across before starting again. Initial costs for rotational grazing systems do tend to be higher for fencing and water distribution supplies for each paddock and this method requires more hands-on management and careful monitoring of forage supply, but there is a long list of benefits to farm productivity, livestock, and birds alike. This system allows for the optimum rest and recovery time of forage species and will provide the highest quality pasture for livestock based on energy, protein, palatability, and digestibility. Other benefits of intensive rotational grazing include weed control, increased grass productivity, even manure nutrient distribution, and more livestock on less land due to increased land use efficiency. In addition to bird diversity, intensively rotated pastures support several times the abundance of grassland birds compared to continuous grazing or even simple rotation (still uses paddocks, but fewer, larger, and less frequently rotated), both of which may create large areas lacking diversity in vegetation structure. Grassland bird habitat is decreasing across the country and each pasture plays a role in providing and maintaining habitat. Below are some examples of small adjustments and actions that may be considered for livestock grazers for grassland birds if they are within the means of farm operations.

Rotation Strategy and Stock Density

Ideal maximum stocking density for birds is difficult to estimate because many variables affect animal unit/acre/time period based on livestock use, breed, age, weight, nutritional demands, forage quality and density, etc. No one size fits all. Audubon is finding that stock density is less important to birds than the time animals have access to an area. Some strategies for rotation include:

- Graze every other paddock (instead of adjacent) to ensure more protective cover and less concentrated disturbance

- Hay or graze areas near trees, roads, and shrubby areas first and delay the center of the grassland (the better nesting habitat) from mowing or grazing as long as possible.

- Change stocking density throughout the season (lower in late spring-early summer during the most crucial and vulnerable time of breeding bird season, then increase in late summer and fall when most birds have had the chance to fledge).

Rotation Timing, Residual Vegetation Height, and Rest Periods

Disturbance frequency and remaining height of vegetation both impact bird reproductive success in grasslands. When livestock are moved to new paddocks frequently, at least every other day, but ideally twice per day, bird nest trampling is minimized. It’s best if the herd is rotated to the next paddock when pasture plant height after a grazing event is ideally still 8+ inches, but no less than 4 inches. As conditions allow, the longer rest periods between grazing events, the better. Ideally 40+ days are needed for many birds to complete a nesting cycle. Bobolinks generally need at least 50 days of rest and Savannah Sparrows need 42 (Perlut and Strong, 2011). At the minimum, after disturbance (grazing or haying), try to give birds enough time to choose a new building site (2 days), build a nest (2 days), lay eggs (5 days), incubate (12 days), and feed the young until they are free flying (9 days) = 28 days, or about a month.

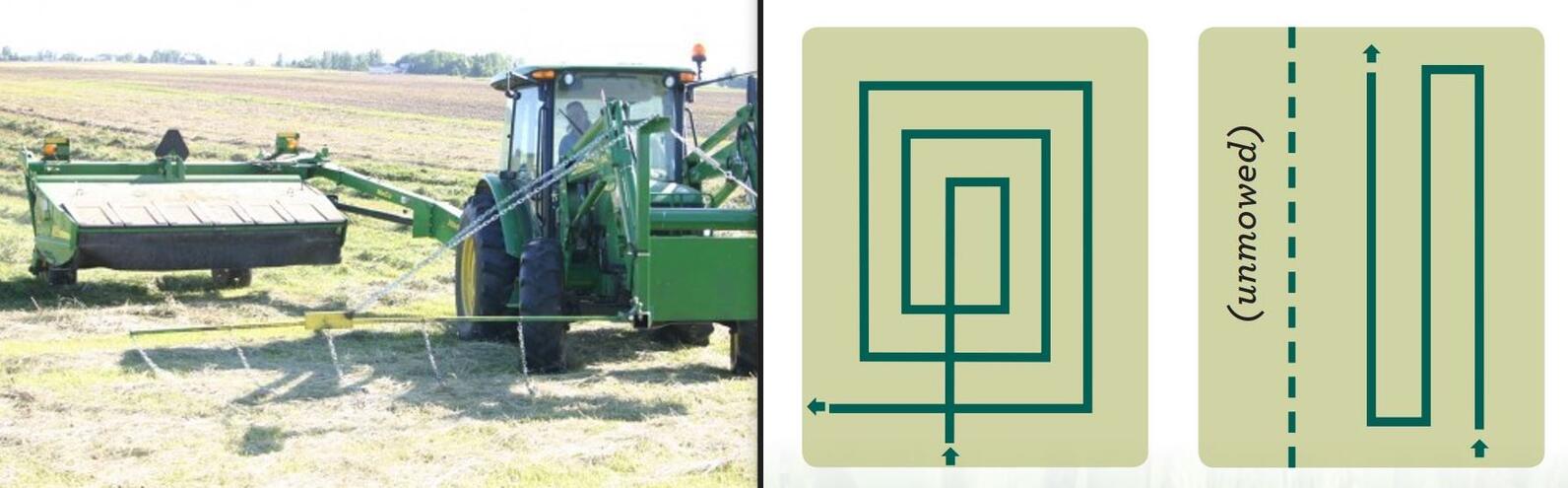

Mowing and Clipping Time Frames to Avoid the Nesting Season if Possible

In addition to grazing, a grassland may also be hayed for winter feed or “clipped” between grazing events to stimulate new growth for the next round of grazing. Cows (and other livestock, especially horses) can be selective about what they prefer to eat, leaving a pasture “patchy” with vegetation of varying heights. When the pasture is cut for hay, it is best that cutting is either delayed until after July 15 (August 1 even better) OR cut early before the end of May and wait until mid-August before cutting again so that the pasture can be undisturbed during the most critical nesting period in June. Another strategy is to use alternative mowing patterns that allow birds a better chance to escape, especially young grassland birds who cannot fly for up to 10 days after leaving the nest. Lines mowed back and forth, starting at one end of the field to the other or mow from the center outwards in a circular pattern. Flushing bars can also sometimes be attached to mowing equipment to warn adult birds before the mower runs over the nest.

Refuge Areas

Sometimes the only viable option for a farmer to create a bird-friendly grassland is to set aside a separate area designated for wildlife habitat. Perhaps this area is not reliably productive, hard to access, more shaded, or more flood-prone. Whatever it may be, the most effective use of this area may be to set it aside for habitat. In that case, a refuge area on a pasture edge or in the center of a pasture can be fenced off for most or all of the nesting season. That area will be most effective if it is not grazed, clipped, or hayed until July 15th. A highly bird-friendly rotational model aims for 33% of all grassland is left ungrazed and uncut from May 15 through July 1. Ideally, the size of refuge should be at least a few acres to allow for a buffer from the fence edge (where birds will not nest), enough space for multiple female nests to a territorial male, and for adequate distance between renest attempts after failure.

Invasive species management for livestock, hay quality and wildlife

Invasive species, such as wild parsnip, spotted knapweed, reed canary grass, buckthorn, and honeysuckle provide poor habitat for many bird and pollinator species and outcompete and replace valuable native flowering plants and forage crops. Specifically, wild parsnip, spotted knapweed, and reed canary grass will make a field inhospitable to grassland birds if not controlled. In addition, wild parsnip is toxic to humans and other domestic animals and spotted knapweed will decrease the hay crop forage quality and sale point. Many of these species can be extremely difficult to control once well-established due to their rapid wide-spread distribution, high seed production, and long-term seed viability in the soil, so a preventative and maintenance approach is usually best. More information about identification and management of these and other invasive plant species is available at https://vtinvasives.org/.

Acknowledging price points and consumer power

It’s important to acknowledge that Audubon has learned organic farmers are often able to grass feed their livestock and manage pastures with more bird-friendly methods than conventional farmers because they receive a higher premium for their milk and meat. This can provide organic producers the financial conditions to adjust their operations while conventional farmers may not have that ability. The higher cost of operations and land space needed for organic farming comes to a benefit to the environment and livestock, but gets passed on to the consumer with more expensive dairy and meat products. This is not feasible for everyone. The higher price of organic products is not always within the financial means of many consumers, but the power in what we decide to buy at the store should not be lost on us. A stronger connection to our food, where it comes from, how it is produced, and with what resources, can ripple into other impacts on the environment and the creatures we share it with.

Overall, rotational grazing has the potential to be a system that supports ground-nesting grassland birds while benefiting livestock. Audubon Vermont’s Bird & Bee Friendly Farming Program will continue working with farmers and partners to find a balanced approach to support farms and wildlife. We are always interested in hearing your opinions and experience; please feel free to reach out to Margaret Fowle or Cassie Wolfanger.