Since 1997, Audubon Vermont has operated a MAPS bird banding station at the Green Mountain Audubon Center. MAPS, a program managed by the Institute for Bird Populations, stands for Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship. MAPS engages NGOs, government agencies, and individuals throughout the United States and Canada in bird banding, a crucial conservation strategy.

In compliance with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the MAPS banding station at the Green Mountain Audubon Center is operated by a USGS-licensed Master Bander, Audubon Vermont’s conservation program manager Mark LaBarr. Mark has handled more than 15,000 birds for banding in his lifetime, including 5,000 birds over 25 years at the Green Mountain Audubon Center.

What is bird banding?

Banding is a way to track individual birds over time. Bird bands are small metal or plastic rings fastened to birds’ legs. Engraved on each metal band is a unique nine-digit number. Researchers might also use colored plastic bands in order to visually identify banded birds without having to recapture them. This method can work well for monitoring birds that will stay in a certain area over a defined study period. Bands do not hurt birds, nor do they impact flight, survival, or reproductive success.

When a banded bird is seen, caught, or found dead, the unique number or color combination of its band can tell researchers when and where that individual has previously been reported. Multiple observations of the same bird over time can lend important insight into its life span, migration routes, habitat preferences, and more. When this information is collected for many birds of the same species or region, researchers can estimate critical demographic variables, like population size, age structure (how many individuals fall into each age range), and birth and death rates. By knowing which bird populations are thriving and which are in decline, researchers can better decide where to focus their conservation efforts.

Banding at the Green Mountain Audubon Center

How do we catch birds?

On seven mornings each year between June and August, 10-12 mist nets are strategically deployed in different habitat types across the lower property of the Green Mountain Audubon Center. These nylon mesh nets, which stand about 10 feet tall and 30 feet wide, are practically invisible under low-light conditions, allowing birds to fly into them and become harmlessly trapped. The birds are then carefully removed from the mist nets and brought to the station for banding and data collection.

What information do we collect?

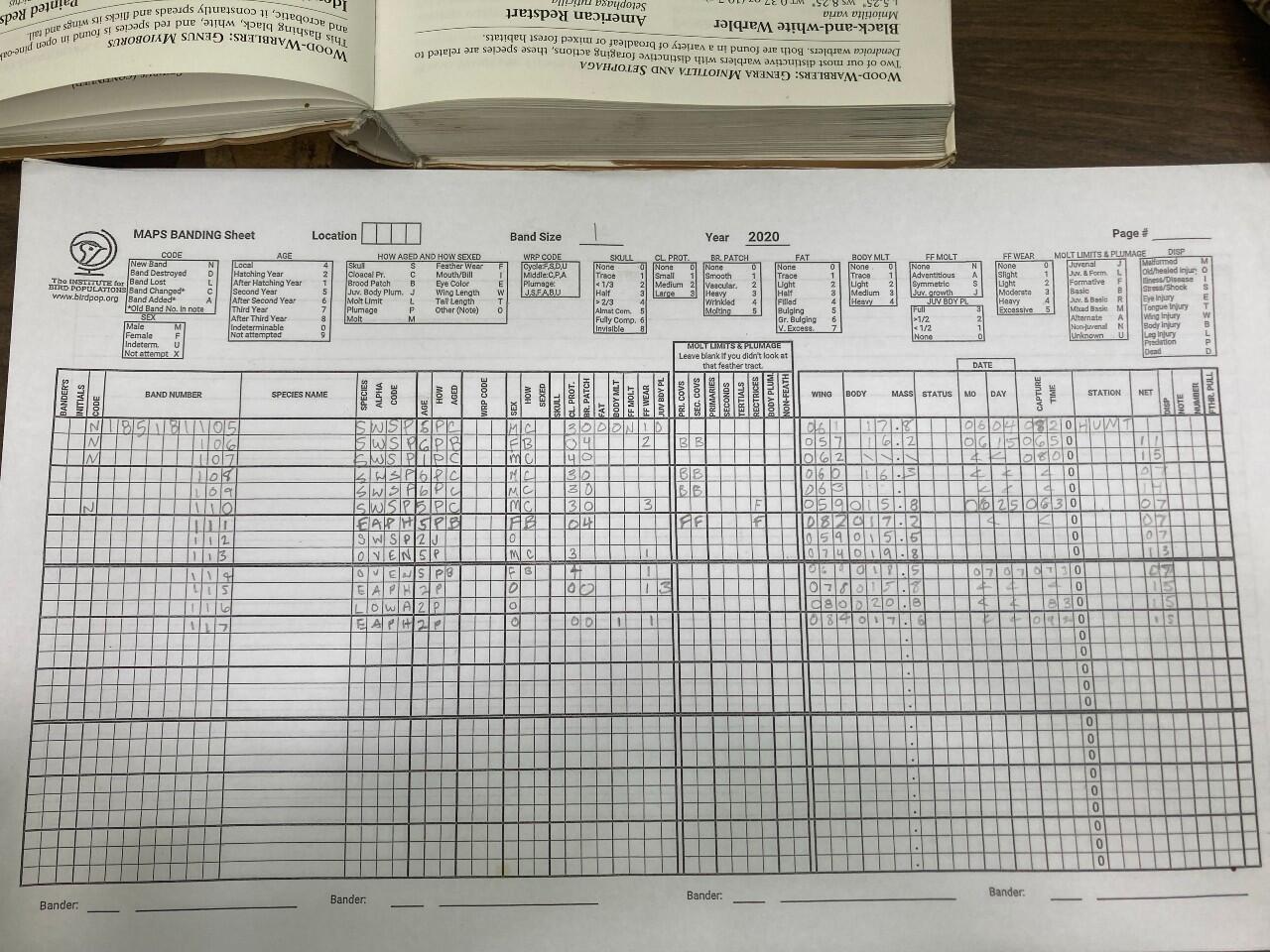

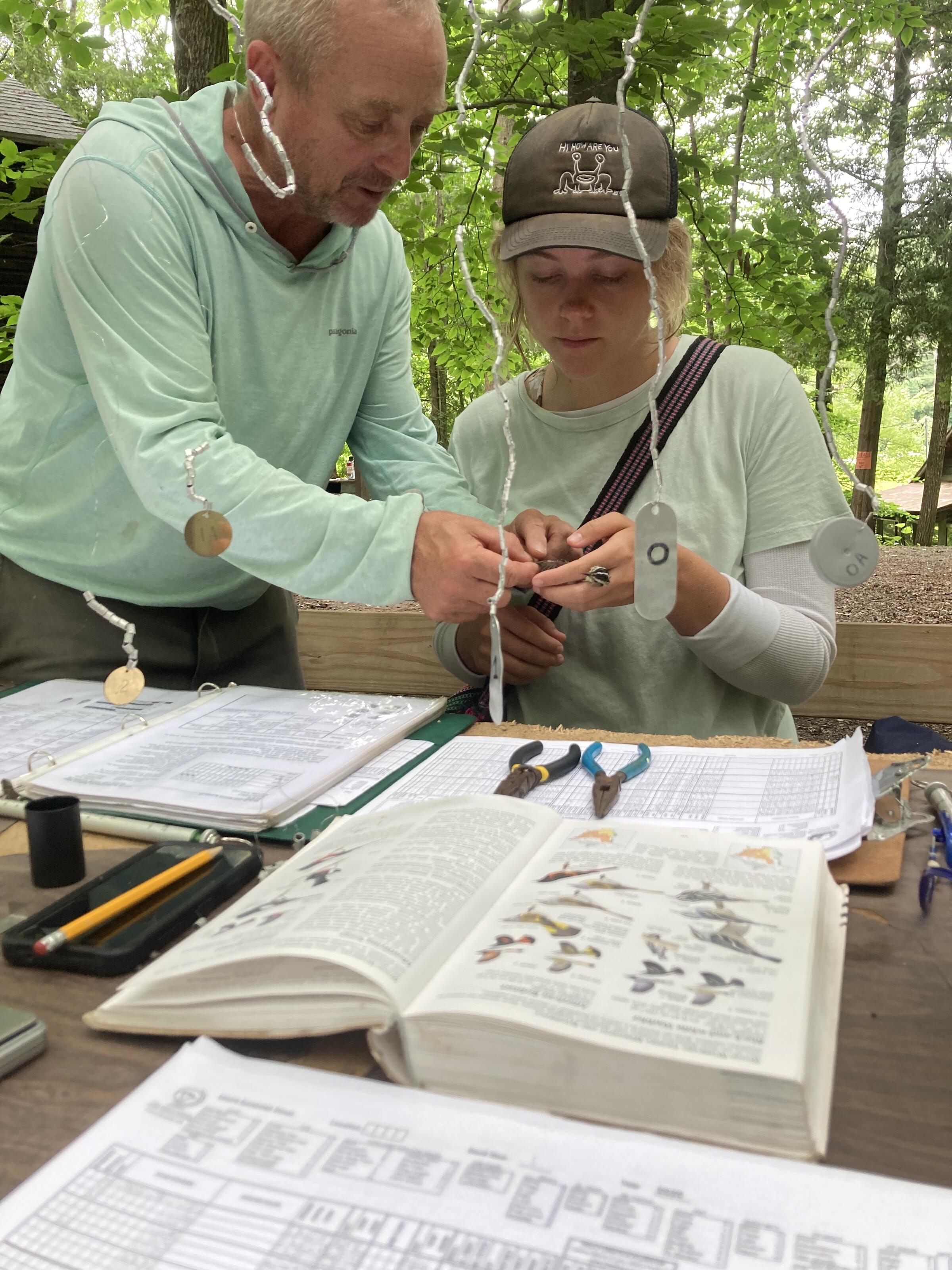

After removing a bird from a mist net, we determine its species, sex, and age. These assessments often rely on intricate details like feather molt, skull structure, and the presence or absence of a brood patch, a featherless spot on females’ bellies used to keep eggs warm during incubation. The cloaca, an under-the-tail opening through which birds both reproduce and expel waste, becomes swollen in males during the breeding season, providing another way to discern a bird’s sex. If the bird already has a band, we record its unique band number. If not, we add an aluminum band of the species-appropriate size using specialized pliers. We also measure each bird’s weight and wing length.

How does this program help conserve birds?

While tracking changes in population size is important, effective conservation requires that we also know the underlying causes of these trends. By gathering advanced data about age and sex, MAPS banding stations allow the Institute for Bird Populations to estimate vital rates, which help reveal these causes. Vital rates include productivity (how many young are produced per adult), recruitment (how many new individuals join the population each year), and survival. These variables help researchers determine which stages of a species’ life cycle are responsible for population declines—and thus where conservation efforts should be focused.

MAPS data, which dates back to 1989, has been used in hundreds of scientific publications. A 2008 report by the Institute for Bird Populations itself found that of 53 species with sufficient MAPS data, nearly 80 percent showed declines in the Atlantic Northern Forest region (which includes the Audubon station) between 1992 and 2003. These included Wood Thrushes, Scarlet Tanagers, Canada Warblers, and Field Sparrows—all priority species for Audubon Vermont.

More recently, this long-term, high-quality dataset has helped researchers investigate the impacts of climate change on bird populations across the continent. For example, a 2020 study used six years of MAPS data from Nebraska to show that Grasshopper Sparrows, an imperiled grassland bird, suffered population declines following rainier springs, while prescribed burns improved their productivity. Grasshopper Sparrows are listed as a threatened species in Vermont.

MAPS data also helps us piece together bird migration patterns and routes. Banding, however, is just one of many tools used to accomplish this. Other strategies include:

-

Radio telemetry: Birds are fitted with small radio transmitters, which send a radio signal to an antenna when the bird flies within range. To improve the frequency of signal detections as birds and other animals travel great distances, the Motus Wildlife Tracking System coordinates researchers who use antenna towers into a global data-sharing network. Click here to view a map of all Motus stations, including several in Vermont.

-

Light-level geolocators: Lightweight devices strapped to birds' backs measure light exposure throughout the day to predict a bird’s location as it migrates. Click here to learn more about Audubon Vermont’s Golden-winged Warbler Geolocation Project.

-

Genetic studies: DNA extracted from feathers can tell researchers when and where birds settle over the winter, and whether populations remain separate as they migrate.

Each strategy has pros and cons, relating to sample size, feasibility, and cost. In tandem, however, they can tell a compelling story about the diverse journeys of Vermont’s birds.

How can I get involved?

Attend public bird banding demonstrations held throughout the summer! Visit our events page for more details.

Special thanks to Audubon Vermont Environmental Conservation Intern Thomas Patti for research, writing, and photography on this webpage.

Related

Banding to Understand the Life of a Bird

Audubon Vermont intern Fiona McCarthy's experience bird banding at the Green Mountain Audubon Center.

Bird-Banding Training

In which Hannah Weiss, the Conservation/Education Fellow, learn the art and science of banding birds

How you can help, right now

Donate to Audubon

Help secure a future for birds at risk from climate change, habitat loss and other threats. Your support will power our science, education, advocacy and on-the-ground conservation efforts.

Visit Audubon

It's always a good time to visit the Audubon Center. Trails are open to the public year-round. Visit us daily from dawn until dusk! Donations are appreciated.

Events

Adults, preschoolers, foresters, photographers, sugarmakers and families will all find opportunities to connect with nature.