Written by Conservation Research Fellow, Cassie Wolfanger. This fellowship is generously supported by Audubon Vermont and Lake Champlain Sea Grant.

What if I told you that the current population of Peregrine Falcons that fly Vermont’s skies and breed here every year is actually a human-induced mixture of subspecies, some of which were not historically present in the eastern U.S. before re-introduction? Maybe you already knew this, but if you’re like me, you had no idea. My interest piqued when Audubon Vermont’s senior conservation biologist and peregrine expert, Margaret Fowle, shared this with me.

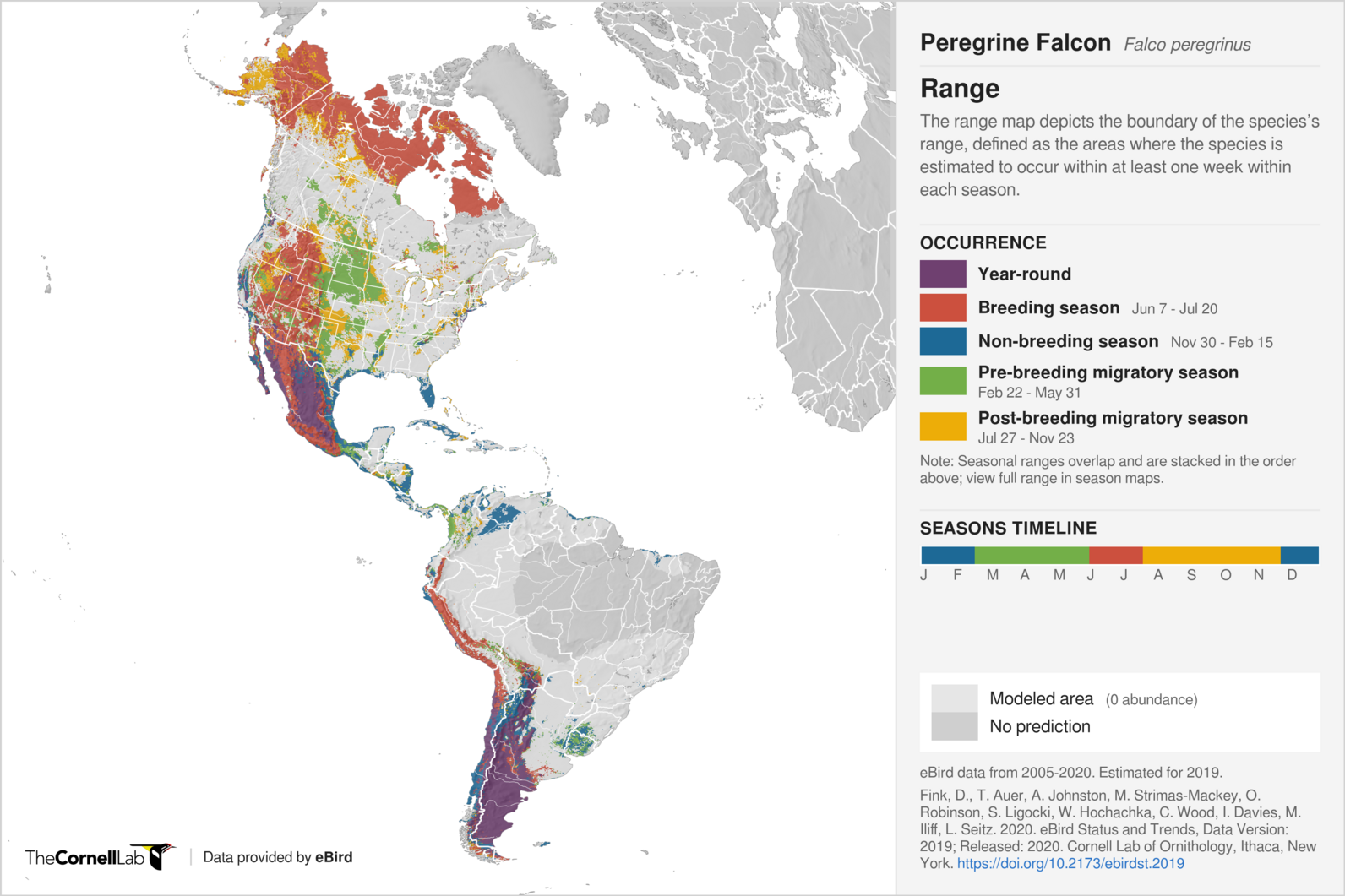

North American Peregrine Falcon migration and wintering grounds can vary wildly. Some individuals that breed in the northeast U.S. remain rather local year-round. Some might only make it to Virginia, while others go all the way to Central and South America. Why is this? It seemed obvious I had to know more about the history of peregrine recovery to understand what might influence their variable migratory behaviors.

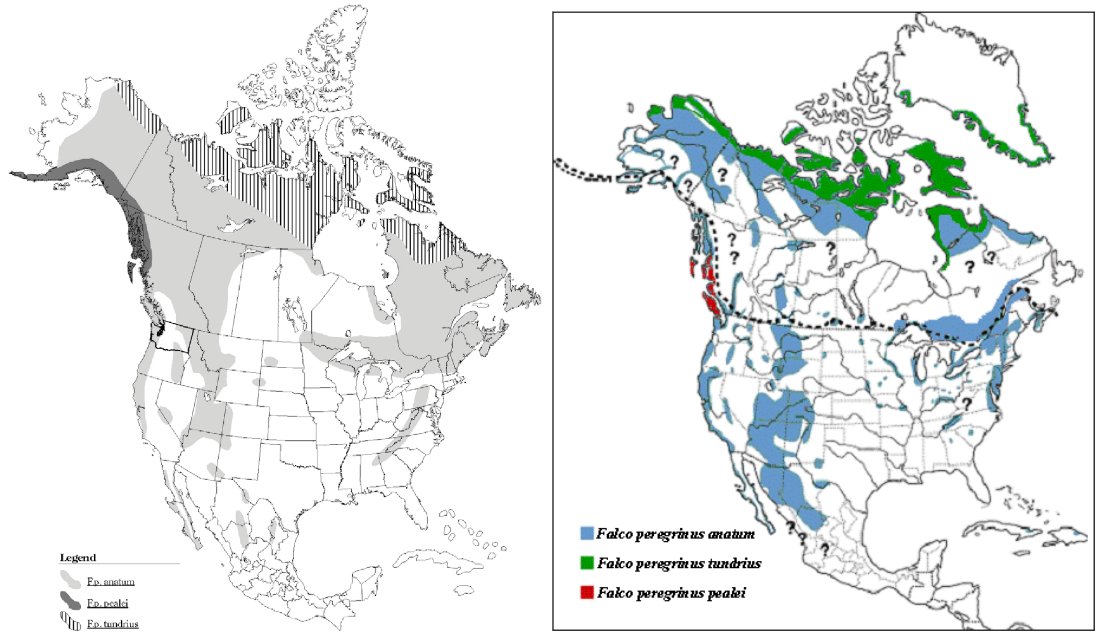

Peregrine Falcons are one of the most widely distributed avian species in the world, existing on every continent except Antarctica. They inhabit mountain ranges, river valleys, and coastlines. Nineteen subspecies are recognized globally, three of which are native to North America: 1) Falco peregrinus (F.p.) tundrius of the Canadian Arctic and Greenland, 2) F.p. anatum, widespread in North America, and 3) F.p. pealei of the Queen Charlotte Islands and Aleutian Islands of Alaska. Thanks to a revolutionary new digital tool from the National Audubon Society and many partners, the Bird Migration Explorer offers an even closer look at the migratory patterns and precise locations of tracked peregrines using the latest conservation science. More on the Explorer later in this article.

A Story of Decline

Historically, the eastern Peregrine Falcon population (an eastern strain of F.p. anatum) was centered in New England and the Adirondack Mountains, ranging south along the spine of the Appalachians to western Georgia. In 1940, the population was estimated around 350 pairs, with at least 32 breeding sites in Vermont. This population, along with many other raptors, soon experienced dramatic declines. The last documented eastern peregrine nesting occurred in southeastern Vermont in 1957 and the species was considered regionally extirpated in the eastern U.S. by the 1960s. Loss of habitat, shooting, egg collecting, and other human disturbances had weakened North American peregrine populations for decades, but the most drastic declines resulted from the widespread use of a popular insecticide—DDT—starting in the 1940s. Its use continued for several decades as DDT was intended to control agricultural pests and malaria-carrying mosquitoes. High concentrations of DDE, a by-product of DDT, disrupted reproduction and prevented normal calcium production, thereby thinning eggshells to the point they would break under the weight of an incubating parent. Raptors at high levels of the food chain, such as Peregrine Falcons, Bald Eagles, and Ospreys, were particularly affected as the chemical built up in their tissues from eating contaminated prey. DDT was eventually banned in the U.S. in 1972, but the chemical persists in the environment and is still used in South America today where some peregrines winter.

An Amazing Recovery

After the Endangered Species Conservation Act was passed in 1969, peregrines were federally listed in 1970 and state-listed in Vermont in 1972. A national effort in the 1980s by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service formed Peregrine Falcon Population Recovery Plans in four regions: Alaska, the Rocky Mountains, southwestern states, and eastern states. Vermont was part of a Northeastern plan along with New York, New Hampshire, Maine, and Massachusetts that aimed to reintroduce peregrines into the wild through captive breeding, protecting essential habitat, monitoring populations, and educating the public. Vermont also formed its own statewide recovery plan in 2000. Between all these efforts, thresholds were set that required the state population to reach minimum numbers of breeding pairs and a minimum average production of fledglings per pair to be maintained for at least five years in order to be considered recovered.

Breeding stock came from falconry birds, injured birds that were non-releasable, and illegally possessed birds confiscated by authorities that also could not be released back into the wild because they had imprinted on humans. Between 1982 and 1987, 93 captive birds were released in Vermont at three sites established in the Green Mountain National Forest: Mount Horrid in Goshen, White Rocks in Wallingford, and Marshfield Mountain in Groton State Forest. The first pair observed to successfully fledge chicks again in the wild was in 1985 at Mount Pisgah in Westmore. By 1999, the species was delisted federally and by 2005, they were removed completely from Vermont’s state endangered and threatened list after a population of 32 territorial pairs were established, reaching the size and range of the recorded historic population. Today’s healthy population has exceeded historical numbers (with more than 55 nest sites in Vermont alone) and has even expanded beyond some of its previously documented range.

The Reintroduction Strategy

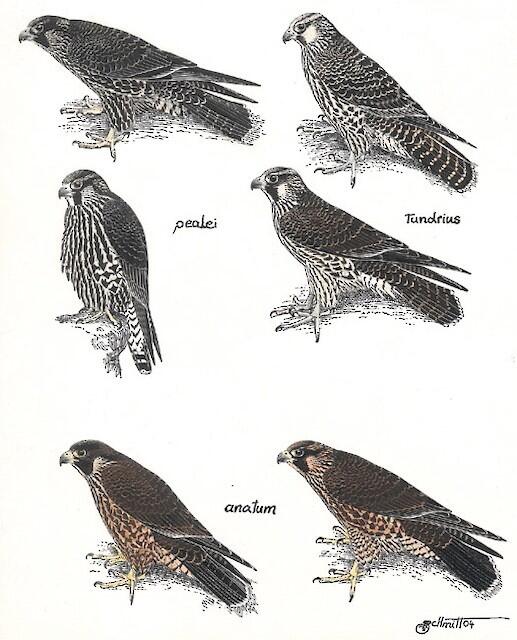

Due to the extinction of the eastern population of F.p. anatum, the near-extinction of anatum in the Midwest, and the limited gene pool within the North American breeding stock, several subspecies were used for reintroduction in order to release as many birds as possible as quickly as possible. That means the post-restoration-era population in the eastern U.S. is a product of a human-manipulated mixture of lineages and is not a subspecies in itself, but instead simply referred to as the “Eastern Peregrine.” Subspecies released in New England, New York, and south through the Appalachian Mountains primarily came from the three native North American subspecies: F.p. paelie, F.p. tundrius, and F.p. anatum. Respective percentages of each subspecies used are unknown. Additionally, four foreign subspecies were also used to a much lesser extent: F.p. peregrinus (Scotland), F.p. brookei (Mediterranean), F.p. Marcopis (southeastern Australia), and F.p. cassini (Argentina). The inclusion of non-native subspecies was intended to optimize the genetic diversity of the released population and increase chances of natural reproductive sustainability.

All of the subspecies used in the reintroduction stock have slight differences in size, color, and body shape. For example, boreal birds are larger than southern birds and extirpated eastern anatum birds were larger than western anatum birds. Other differences reside in behavior such as hunting, flying, and yes, even migration. Although we can sometimes generalize the typical migratory pattern of each subspecies, geographical boundaries of different subspecies’ ranges overlap considerably, and they display a graduation from one lineage to another, especially when multiple occur on a single continent like North America. There is also variation among individuals within the same population.

Peregrines’ Wildly Variable Migration

Peregrine Falcons can range from being considered non-migratory, long-distance migrants, or somewhere in between, depending on subspecies. On a continental level, peregrines appear to exhibit a “leap-frog” movement where the northernmost breeding birds in the artic travel farthest south to overwinter, jumping over their counter parts at lower latitudes that might only travel to the mid-southern U.S. or Mexico. Further still, many individuals defy this trend, staying exactly where they are as year-round residents. F.p. tundrius, the artic subspecies, engages in the longest migration of any North American subspecies of peregrine and any North American raptor for that matter. F.p. anatum and paelei are moderately migratory and some brookei and cassini are rather sedentary. Since the current eastern U.S. peregrine population is comprised of multiple subspecies, it’s interesting to wonder if the genetic coding of dominant lineages influences migratory behaviors.

Of the peregrines that do make the journey, spring migration typically peaks in April and fall migration in October. Although usually solitary migrants, some fledgling siblings may travel together in fall. Travel routes are concentrated along defined flyways, especially coastal areas of prime habitat with open spaces for hunting. Using the new Bird Migration Explorer Tool from the National Audubon Society and many collaborative partners, you can see migration patterns, routes, and timing from 38 tagged peregrines. Watch the graphic below to see how peregrines move from breeding grounds in Alaska, western Canada, the Rocky Mountains, and mid-western U.S. by traveling south through Texas to the Gulf of Mexico and eventually to Central and South America. Birds breeding in Greenland, eastern Canada, and some in the northeast U.S. appear to travel down along the Atlantic coast, to the Florida Keys or the Caribbean. Some continue to Central and South America, while some birds in the north eastern U.S. region don’t migrate at all!

Tracking Peregrine Movement

Migratory pathways for 38 tagged Peregrine Falcons over the course of Jan-Dec calendar year from the Bird Migration Explorer.

In addition to differences between subspecies, there are likely several other factors influencing movement of peregrines, including food availability, age, sex, and natal nest setting. Due to human manipulation of nest site selection by releasing birds on bridges, buildings, smoke stacks, towers, and other human-made structures during re-introduction, peregrines’ current use of urban sites for nesting has become widespread, where the species only rarely nested in those areas prior to re-introduction. Most northern New England nests in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine are located on rock cliffs, including human-created cliffs (e.g., road cuts, quarries), whereas the majority of southern New England nests in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island are located on buildings and other human-created structures. Interesting! Urban peregrines have ample year-round food supply in the form of Rock Pigeons and other urban dwelling birds when many rural natural cliff-nesting peregrines, especially in more severe weather regions in the north, must migrate in order to find sufficient prey. Could winter food availability override the instinct to migrate if it was common in their ancestor’s subspecies? Research on banded and tagged northeastern peregrines between 1990 and 2009 suggests juvenile birds are more likely to migrate farther than adults, females disperse more than males, and most peregrines show a strong fidelity to the nest type on which they were raised (Faccio et al. 2013). If the recovery story of Peregrine Falcons has taught us anything, it is that we can’t always put individuals in neat categorical boxes of behavior, subspecies, or geographical range. The genetic makeup of the current breeding population matters less than the will of this highly adaptable species to survive against great odds.

Future Peregrine Conservation and the Bird Migration Explorer

Peregrines are doing well, but are still subject to disturbance, especially from rock climbing and hiking. Continued monitoring of high-traffic sites, seasonal cliff closures, and long-term breeding site protection will help ensure survival. Currently, Peregrine Falcons are federally protected from hunting and other forms of “take” by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Species restoration, like habitat restoration, is usually a compromise between the ideal return to the original pristine condition and the practical limitations of what is possible in a drastically altered, human-dominated landscape.

You can learn more about Peregrine Falcon migration and what conservation challenges they are facing across the northern and southern hemispheres with the Bird Migration Explorer—the first free, interactive digital platform that combines multiple types of migration data for over 450 bird species that breed in the U.S. and Canada. Take a look at: http://www.birdmigrationexplorer.org

Learn more about Vermont’s Peregrine Falcon recovery efforts at: https://vt.audubon.org/peregrine

Resources

Cade, Tom J., James H. Henderson, Carl G Thelander, and Clayton White. 1988. Peregrine Falcon Populations: There Management and Recovery. The Peregrine Fund, Inc. Boise ID. Printed by Braun-Brumfield, San Francisco, CA.

Cade, T., H. Tordoff, and J. Barclay. 2000. Re-introduction of peregrines in the eastern United States: an evaluation.

Faccio, S.D., M. Amaral, C.J. Martin, J.D. Lloyd, T.W. French, and A. Tur. 2013. Movement Patterns, Natal Dispersal, and survival of peregrine falcons banded in New England. Journal of Raptor Research 47(3) 246-261.

Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, W. Hochachka, C. Wood, I. Davies, M. Iliff, L. Seitz. 2020. eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2019; Released: 2020. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://ebird.org/science/status-and-trends/perfal/abundance-map-weekly

Fowle, M.R. (2000) Vermont Peregrine Falcon Recovery Plan. National Wildlife Federation, Northeast Natural Resources Center, Montpelier, Vermont 05602.

Holroyd, G.L., and D.M. Bird. 2012. Lessons Learned During the Recovery of the Peregrine Falcon in Canada. Canadian Journal of Wildlife Biology and Management. http://p.behr.free.fr/biblio/holroyd2012.pdf

Ratcliffe, Derek. 1993. The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd Ed. Academic Press Inc. San Diego CA.

Rowel, P. and D.P. Stepnisky. 1997. Status of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) in Alberta. Alberta Environmental Protection, Wildlife Management Division, Wildlife Status Report No. 8, Edmonton, AB.

Smith, Melanie A., John Mahoney, Erika J. Knight, Lotem Taylor, Nathaniel E. Seavy, O’Connor H. Bailey, Marco Carbone, William DeLuca, Nicolas S. Gonzalez, Miguel F. Jimenez, Gadalia M. W. O'Bryan, Nalini Rao, Chad J. Witko, Chad Wilsey, and Jill L. Deppe. 2022. Bird Migration Explorer. National Audubon Society, New York, NY. birdmigrationexplorer.org.

Wheeler, Brian K. 2003. Raptors of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

White, C. M., N. J. Clum, T. J. Cade, and W. G. Hunt (2020). Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.perfal.01

White, C. M., N. J. Clum, T. J. Cade, and W. G. Hunt (2020). Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. 2015. VT F&W Action Plan (2015). Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. Montpelier, VT.