Audubon Vermont hosts conservation, education, and policy interns every semester. Interns provide an intern's-eye view of the exciting and important work being done by Audubon Vermont every day. Pete is one of Audubon Vermont's Conservation Interns for Summer 2025. Check out our alumni page for more information and stories!

__

Staring into the trees on an early morning, I was greeted by an ancient song – it drifted, echoing through the fog, slipping through emerald hemlock needles and down the creek. Among young beech and maple trees, the music touched anyone willing to listen. Its energy is invisible, but alive in anyone who enters the forest on a summer day.

A Wood Thrush is not like the Arctic Tern who makes long voyages between Earth’s poles. Instead, Wood Thrush travel a humble 2,000 miles between their breeding and wintering grounds. Throughout their journey, and at their destinations, these birds require specific habitats. According to Cornell Lab of Ornithology, when Wood Thrush winter in southern Mexico and Central America, they are most abundant the interior of mature, shady, broad-leaved and palm tropical forests in lowlands (All About Birds). During breeding season, Wood Thrush prefer mature deciduous or mixed forests with tall trees and a dense understory for foraging and nesting. Unfortunately, both of these habitats are experiencing fragmentation which leads to limited access to quality food and shelter. As such, scientists have noticed a decades-long trend of population decline.

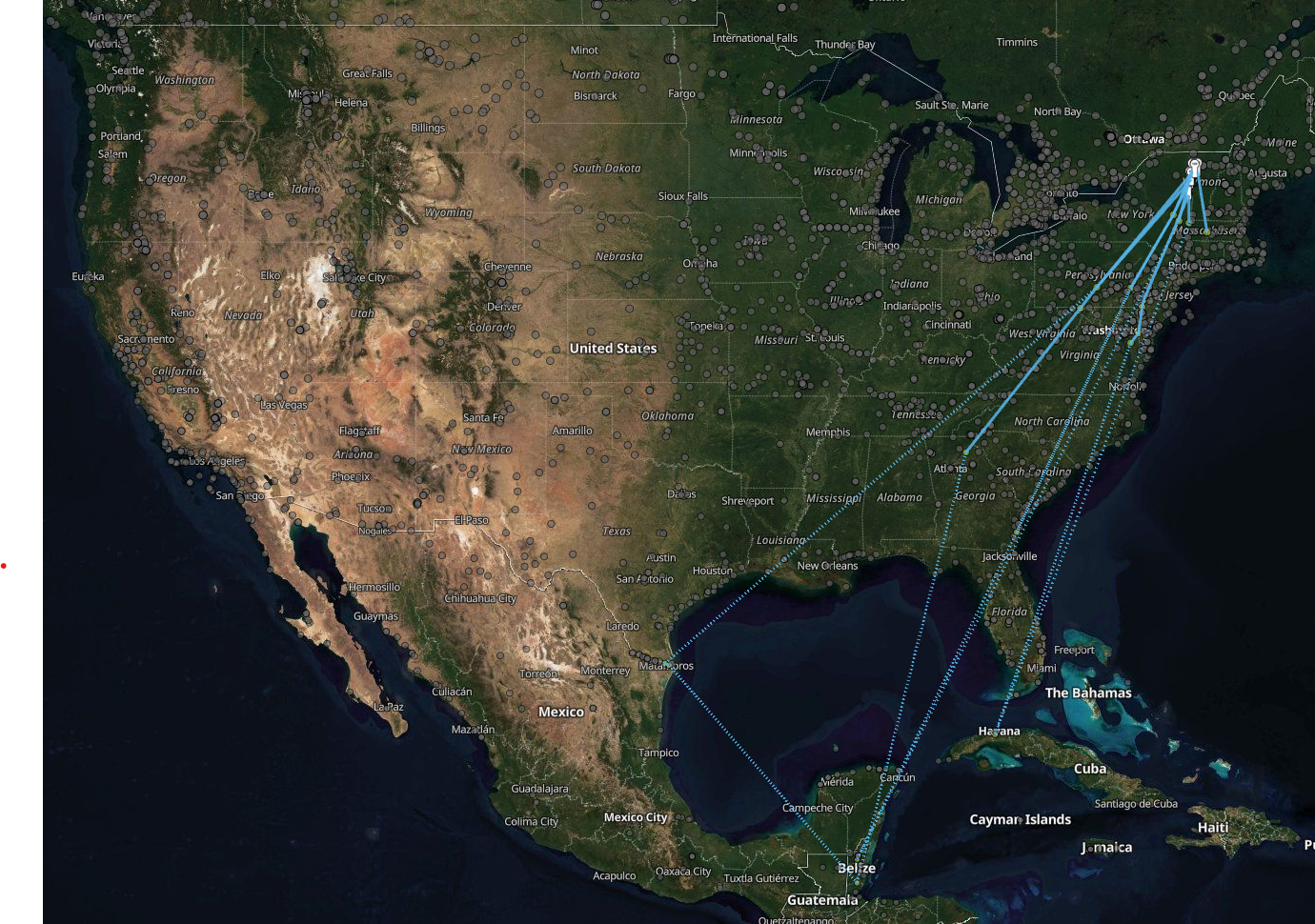

In response to this decline the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recruited bird banders and organizations, like Audubon Vermont, for the Wood Thrush Nanotagging Program, colloquially named WOTH Party. WOTH Party is a two-year study that tracks the movements and behavior of Wood Thrush in their breeding and wintering grounds using nanotags. Nanotags are small, lightweight transmitters that are carefully fitted on the backs of the birds by trained professionals. Two wire loops slip over each of the bird's legs so that they are essentially wearing the transmitter like a backpack! Nanotag signals are received by Motus Wildlife Tracking System (Motus), a network of 1,200 radio receiver stations across 31 countries. When a tagged Wood Thrush flies within 12.4 miles of a Motus tower, its nanotag will “emit individually unique, digitally encoded radio signals that broadcast up to several times a minute on a shared frequency on all Motus stations in the world” (US Fish and Wildlife Service).

Declines in Wood Thrush populations have been especially prevalent in the northeastern regions of their range, with an overall population loss of 59% since 1970. Nanotags were deployed across its range in both North and Central America in hopes of understanding migration routes, timing, and survival to inform targeted conservation efforts, address population declines, and strengthen international collaboration. The data will help identify key habitats and guide management actions to support the species’ recovery.

This summer, I have been interning under Mark LaBarr, Audubon Vermont’s Conservation Program Manager, as a Priority Bird Species Intern. During this time, we have traveled far and wide toting mist net poles, nanotagging equipment, and bug spray. We battled black flies and mosquitoes on Snake Mountain, encountered weary Wood Thrush in Waltham, and met overly eager Wood Thrush in West Haven, who bounced out of the mist nets rather than into them.

The process of nanotagging Wood Thrush involves locating areas where the birds are present. Once identified, we play the Wood Thrush song to attract the birds to a specific area or to confirm their presence. Afterward, we set up two mist nets with a Wood Thrush decoy in the middle and a speaker playing the song. The idea is that a male Wood Thrush will see the decoy and hear the song, prompting him to approach and “chase” the decoy out of his territory. While easier said than done, some birds arrive within minutes, while others may not come at all or take hours to fly into the net.

Once a bird is captured, the real work begins. First, the bird’s weight is measured; if it meets the necessary criteria, the tag must be activated and function properly, which is verified with a special device. Afterward, the harness is prepared to ensure it fits the bird correctly. Mark, who works under proper federal permits and training, constructs the harness by weaving the material through the tag, creating two loops—one for each leg. Once fitted, the harness is crimped, and any excess material is cut. Data such as the tagging site, band number, tag number, sex, age, and weight are recorded. The harness and tag do not hinder the bird’s ability to fly, so once all procedures are complete, the bird is released. If the bird falls within a certain radius of the Motus Tower, the signal within its tag will be detected and update the Motus database, allowing researchers to track and view the individual bird’s migration in real time as well as after the cycle is complete.

Over the past two months, we have nanotagged 12 Wood Thrush across Vermont – four of which were caught during MAPS banding sessions, which stands for Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship. Two of the Wood Thrush tagged during MAPS were juveniles, along with an adult male and female. The prevailing speculation is that these birds were a "family" group. The male from this group has already left Vermont and was detected in Massachusetts on July 27, 2025. We are hopeful that these birds will return to the forests surrounding the Green Mountain Audubon Center next summer.

Last summer, six Wood Thrush were tagged by Mark LaBarr and his intern. Of those six, three returned to Vermont this summer. "Debbie," tagged in Shelburne, VT in June 2024, was detected in Shelburne in May 2025. Another, tagged at Charlotte Park and Wildlife Refuge in June 2024, was also detected returning to Vermont, this time at the Dead Creek Motus Tower in May 2025. Another Wood Thrush was spotted by Mark and I at the Helen W. Buckner Preserve in June 2025. This last bird is presumably the same that was tagged at the Buckner Preserve last summer, which migrated to Havana, Cuba, and then returned this year.

Similar to the migration of a Wood Thrush, Mark LaBarr ventured south to tag Wood Thrush at La Milpa Ecolodge and the Toucan Ridge Ecology and Education Society (TREES), located in Belize. While none of the birds he tagged migrated to Vermont, they did return to areas across the United States, which emphasizes the cross-continental connection these birds create during their migration and how collaboration is key to studying and managing bird populations.

This past school year, I took a year-long course at University of Vermont (UVM) called Fellowship in Restoration Ecology and Cultures (FREC). During this program, my peers and I gained a strong understanding of restoration ecology and developed restoration projects at Carse Wetland, a UVM Natural Area in Hinesburg, Vermont. During the first week of my internship, we got to spend some time at Carse Wetland to nanotag a Wood Thrush! Coincidentally, one of the projects I was involved in during the course focused on understory regeneration in the forest above the wetland. Although the plantings we implemented won’t develop into understory for several years, knowing that our efforts will create habitat for this Wood Thrush in the future instills hope in me for the populations recovery and creates a meaningful connection between the work we did and this internship.

While this study is coming to an end, the data collected over the past two years will be invaluable in informing management decisions and conservation strategies, ensuring that these vital habitats maintain the ability to support Wood Thrush and it’s beloved song.