Just as birds need healthy forests and grasslands, protected wetlands, and connected floodplains for habitat, Vermont’s human communities need those same landscape features to survive the onslaught of weather shifts caused by global climate disruption. Is it too soon after the July 2023 flood disaster to look ahead to the next flood coming to Vermont? Is it too soon to ask whether we should increase our investment in protecting nature’s own flood relief valves given the limits concrete infrastructure such as floodwalls and other flood barriers may have on controlling rivers?

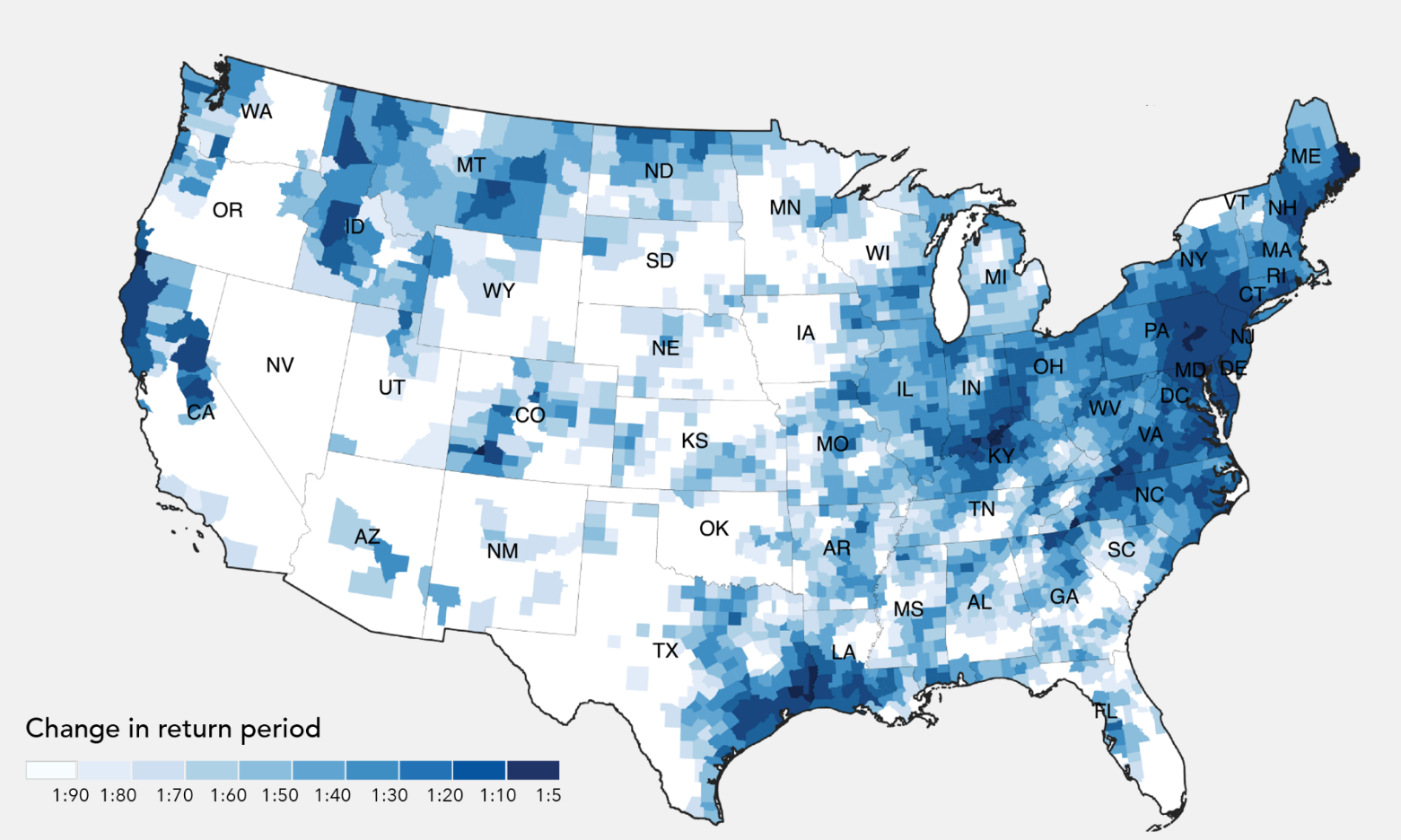

The climate crisis is here and Vermont is no exception as we experience more frequent and severe storm events. According to the 2021 Vermont Climate Assessment, our state is declaring an average of 1.4 major flood disasters per year and a 21% increase in annual precipitation since 1900, which poses significant health, safety, and financial impacts for Vermonters. Nationwide, a recent study predicts the Northeast will continue to get wetter into the future, despite its reputation as a climate haven. Roughly 21% of the country can now expect a severe “1-in-100-year flood” event to happen every 25 years, with some of the most extreme cases – over 20 counties in the United States, that are home to over 1.3 million people – expected to experience the current “1-in-100 year flood” at least once every 8-10 years.

In the fall of 2011, Vermonters were necessarily and appropriately focused on helping the many people and businesses displaced and harmed by the catastrophic statewide flooding caused by Tropical Storm Irene. Even then, however, as the depth of the human tragedy unfolded, there were quiet conversations in which many Vermonters began asking whether we should re-think the ways in which we live on the land. Comparisons between flood damage of 1927 and Tropical Storm Irene were made (the 1927 flood damage was far worse) and we wondered if the increase in Vermont’s forest cover and protections of wetlands made a difference in reducing flood damage.

In the years since Tropical Storm Irene, historians and scientists have confirmed those suspicions. Massive deforestation and beaver trapping in the 1800s led to increased flash floods because there were no trees on the landscape to intercept and slow rainwater, wetlands were drained for development, and rivers were channelized and cleared of natural woody debris for quick and convenient log transport. With the dramatic change in the landscape today since that period, environmental scientists at the University of Vermont and Vermont Agency of Natural Resources have studied and documented the ways in which past investments in the natural features of Vermont’s landscape reduce the harm to Vermont’s communities.

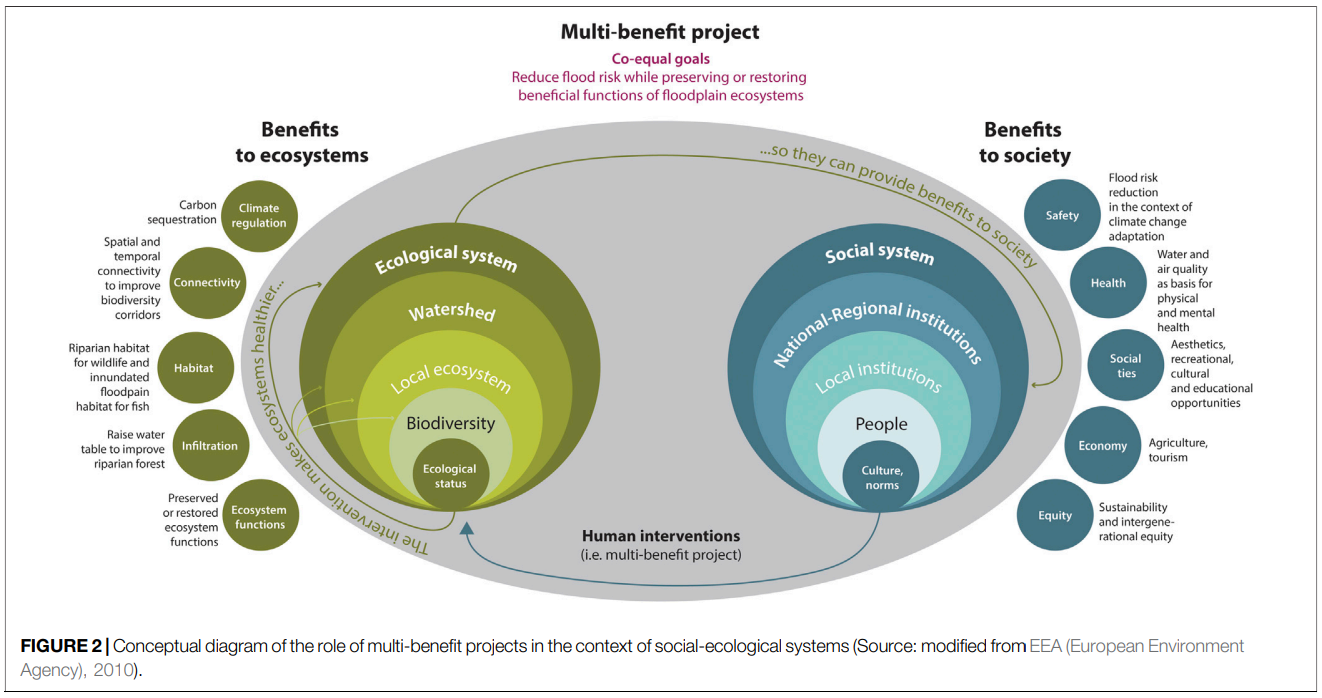

Frequency and severity of flooding is influenced by three major factors: the amount and timing of precipitation, the condition of the basin's stream channels and floodplains, and the timing and rate of storm water conveyance off the watershed. The latter two factors may be the only ones we have any real influence on with the decisions we make on-the-ground because they are partly a function of soil condition, extent of impervious surfaces, and health of ecosystems. Often referred to as “climate natural solutions,” actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore ecosystems, provide multiple co-benefits to human wellbeing and biodiversity alike.

This nature-based approach to flood storage relies on relatively low-cost, low-maintenance conservation practices that increase the density of vegetation cover in a watershed, intercepting rainwater, and retaining it for longer periods on the upland landscape along with sediments and pollutants. Restorative strategies can include protecting wetlands, giving rivers full access to their floodplain (i.e., letting floodplains flood and allowing them to meander at will), planting forested buffers, reducing mowing, and incentivizing agroforestry.

Floodplain forests are ideal habitat for many songbirds including woodland warblers, flycatchers, Wood Ducks, and other cavity-nesting birds that need snags (or bird boxes) to raise their broods. Many of the indigenous tree, shrub, and understory plant species selected for bird habitat enhancement in riparian areas, such as willows and dogwoods, are fast-growing, water-loving, and bank-stabilizing. Just this past year, conservation organizations in Vermont planted 5,500 trees to protect against flooding and boost clean water in Lake Champlain, most of which held up well to the July storms.

The land currently protected from development or managed as forests, farms, and fields, and the wetland and natural floodplain features they include are critical to the ecological health, public safety, and prosperity of our communities. Not only do these features of our landscape provide habitat for birds and wildlife, reduce water pollution, recharge groundwater, and store carbon -- they also reduce the impact of floods on the houses, businesses, roads, bridges, pipelines and other infrastructure in our communities.

Following Tropical Storm Irene, the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) has lead and coordinated efforts by local, state and federal agencies to advance climate natural solutions. For example, ANR runs an education program to promote community flood resiliency called Rivers and Roads in which state biologists train members of the Vermont Agency of Transportation on how to do roadwork in a way that is more compatible with functioning streams and rivers. Other efforts, such as the Stream Wise program, have been supported and implemented by municipalities, private landowners, businesses, non-profit organizations, and volunteers. Further, Vermont policy leaders have recognized the value of further investing in climate natural solutions in the Vermont Climate Action Plan. The recently enacted Community Resilience and Biodiversity Protection Act, requiring the development of a state plan to conserve more land, is premised in part on the recognized connection between investments in wildlife habitat and community resilience to climate related disasters. These plans, still under development, are moving in exactly the right direction. They are, however, just plans.

We are inspired by the response of Vermonters to the plight of our neighbors, friends, and families impacted by the July 2023 floods. We should focus on these vital humanitarian needs first. Recalling, however, that Tropical Storm Irene occurred just over a decade ago, it is not too soon to start the discussion about how we move beyond planning and words into action – and about how we accelerate and expand the critical work Vermonters have been engaged in for decades to protect, restore, and enhance the health of our landscape.

At this moment, there are unprecedented levels of federal funding available to Vermont to invest in the protection, conservation, and ecologically-minded management of Vermont’s fields and forests. The clear message from this most recent extreme flood in July that the next flood may not be too far in the future. How we respond to that message will determine what our resilience in the future looks like. An approach that goes beyond engineered flood control structures to grow our investment in nature-based climate solutions is a critical and proven component of that response. The time to act is now.