What do you already know about beavers? What do they look like? Where do they live? What do they eat? Did you know beavers can help restore ecosystems? Get ready to learn all about beavers!

Beavers are mammals and the biggest rodents we have in the United States, weighing between 35-65 pounds. Beavers are often referred to as 'nature's engineers' because of the complex systems they create when building dams and lodges. They are constantly maintaining these structures unless they are iced in or environment conditions change and the beavers move on to a new area. At the Green Mountain Audubon Center we used to have beavers living in our Beaver Pond. However, a landslide occured within the last five years that filled much of the pond with sediment and drove the beavers away. Even so, you can still find evidence of beaver chews along the sugar bush trail.

A Short History of Beavers

Beavers have had a rough history in our country. Before European settlement in the 1800s, the beaver population in New England was believed to be ten times larger than it is now. Settlers had began clear-cutting forests for farm land and trapping beavers for the fur trade, which nearly caused their extinction. Starting in 1910, beavers became protected by Vermont state law and the population slowly grew, but not even close to what it used to be. To help the population grow, beavers were reintroduced into Vermont in the 1920s and within 20 years their population became well established (VT Fish & Wildlife).

Beaver Anatomy 101

Beavers have several physical adaptations that allow them to thrive on land and in water.

- Hind, webbed feet: Beaver's hind feet are webbed, which helps propel them through the water. Beavers can swim up to ~5 mph!

- Strong teeth: Perhaps the most well known feature of a beaver is its buckteeth. Beavers are rodents, which mean they have incisor-like teeth. These teeth do not stop growing, but the beaver's gnawing keeps them chiseled. Beaver teeth make it possible for a beaver to eat bark and fell trees in a matter of minutes.

- Tail: Beavers have a wide, flat, scaly tail that acts as a rudder while they swim. The tail also stores fat that helps beavers to regulate their temperature. When beavers sense a threat they slap their heavy tail against the water to startle a predator and/or warn other beavers of danger!

- Fur: Beaver fur is thick and contains a water repellent oil, castoreum, which they reguarly comb into their fur with their preening toe. This helps them conserve heat in freezing water and keep their skin dry.

- Eyes, nose, ears: Beavers have a special inner eye-lid, called the nicitating membrane, that allows them to keep their eyes open underwater and protect their eyes. Beavers can also close their ears and nostrils while underwater. These adaptations help beavers swim underwater for up to 15 minutes!

- Thick layer of fat: Beavers have a thick layer of fat right beneath their skin that helps insult, or keep their body warm. This is especially important in winter and cold water.

Acitivity 1: Swim like a beaver!

Learn what it feels like to have webbed feet in this activity!

You will need:

- Plastic sandwich bag (really any size could work)

- A sink or large container full of water

Steps:

1). Drag your fingers around in the water and describe what it feels like. Are you able to move easily in the water? Make a prediction: are humans or beavers better adapted to be swimmers?

2). You will simulate how it feels to have webbed beaver feet in the water! Place your hand in the plastic bag, spread your fingers apart and drag the bag through the water the same way you had with your bare hands. Does this feel different? Was your prediction correct?

Nature's Engineers: Dams and Lodges

When choosing an area to live and build their lodges and/or dams beavers look for areas of flowing water where the volume of water is reliable or still waters where water levels are consistent (VT Fish & Wildlife). Just as important are the kinds of trees growing near that water; beavers depend on trees for both food and shelter. Beavers prefer to eat the inner bark of hardwood (deciduous) trees, such as beech, but when it comes to buidling materials, they aren't so picky.

Lodges

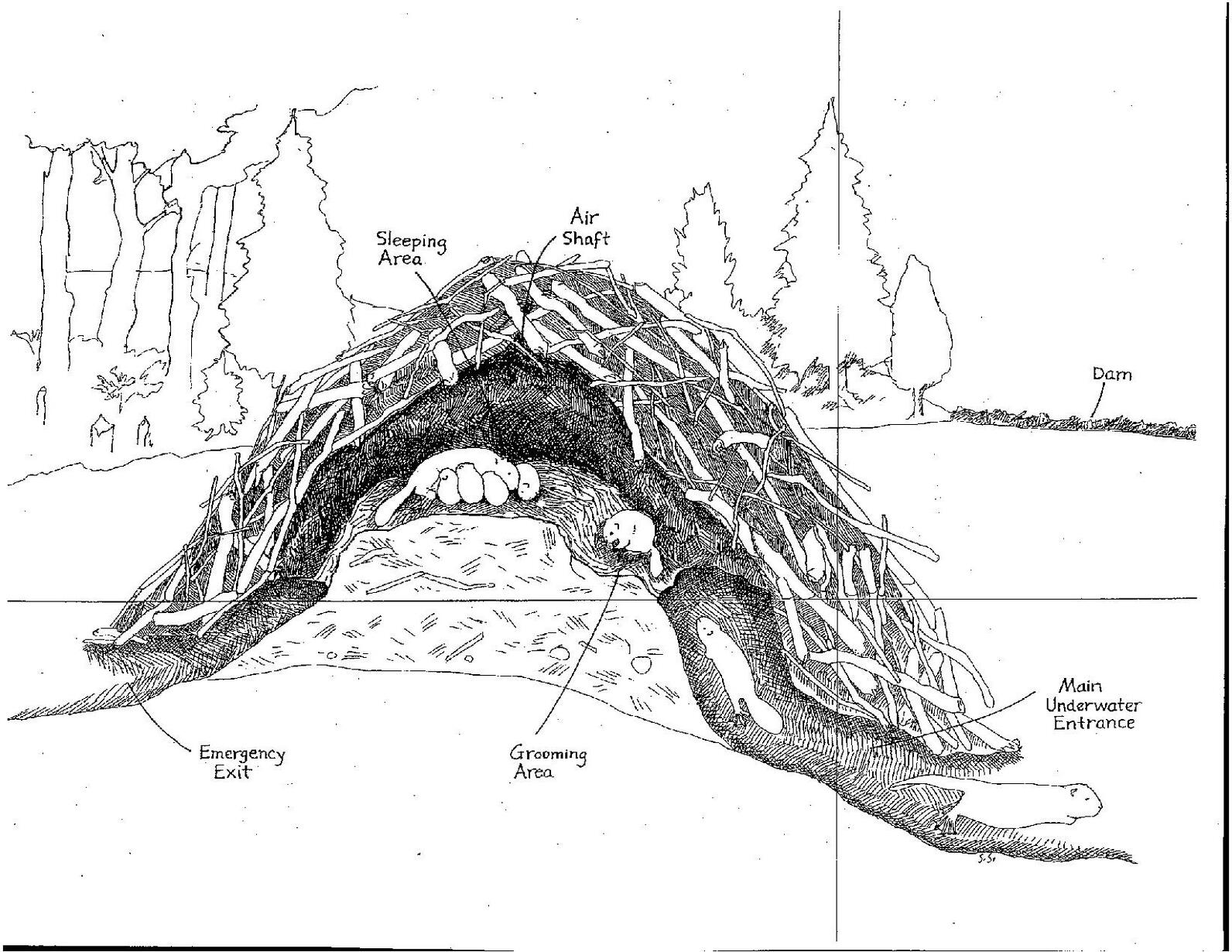

Lodges tend to be dome-like and constructed out of sticks, mud, stones, leaves, grass and sod. Beavers start building their lodges by piling sticks in the water. Beavers swim up from underneath the pile to start hollowing it out to make a living space. This living space is built above waterline and is connected to the outside with usually two underwater tunnels (VT Fish & Wildlife). To make the central living area cozy, beavers will line it with bark and grass. If you look carefully at a lodge, you will also notice a hole at the top that allows for ventilation in the lodge.

Dams

Dams allow beavers to manipulate their environment to create habitat. Dams trap water flow until a new body of water is created, a 'beaver pond.' These ponds can be very large and not only do they allow beavers to access food more easily without needing to stray far from the water, but they also provide ample habitat for other aquatic critters. Their dams, by flooding woodland swamps, help restore important wetland habitat and ecosystem function! At the Green Mountain Audubon Center, our beavers have moved on from their pond, but the pond remains important habitat for turtles, crawfish, salamanders, frogs and aquatic invertebrates.

Activity 2: Build your own beaver dam!

You will need:

- Building materials collected from outside (sticks, rocks, grass)

- Access to running water i.e. stream, brook, runoff (bring container of water outside if needed)

- OPTIONAL: Use a plastic bin to build your dam in if you are unable to go outside beyond your yard or park!

Steps:

- To preapre, collect sticks, rocks and grasses in your yard or local park that are dead, browned and down. This means we are not collecting anything living.

- Once you have your materials, choose a spot to build your dam! I found a spot in my local park where runoff had pooled and started a stream. A spot with mud will work best! Mud is the glue that will hold your dam together. (If you don't have mud you can build your dam the best you can with the materials you do have)

Nice and muddy! Photo: Sarah Hooghuis/Audubon Vermont - Start building your dam! Remember, you want to build something strong enough that it will trap water!

I started building my dam with leaves and sticks. Photo: Sarah Hooghuis/Audubon Vermont

Next I added a bunch of mud until I noticed the water stopped trickling out of the pool. Photo: Sarah Hooghuis/Audubon Vermont - If you are using a bin to build: put your dam to the test! Fill a large container of wate and pour the water on one side of your dam. Did the water flow through or get trapped?

- Try again! Test different materials and designs until you think you have created your best beaver dam.

We've learned so much about beavers! Let's put all our knowledge together and sing this song!

"I’m a Little Beaver”

I’m a little beaver, short and stout.

Here is my tail and here is my snout;

If I chew a tree down then I’ll shout,

"Not to worry ‘cause it‘ll re-sprout!

Optional:

- Go for a nature walk and look for a beaver dam or signs of beavers!

- Watch our puppet show on Youtube about animal homes featuring a beaver

- Make your own beaver with the cut out craft attached below

Attachments: